In the charismatic church I was part of in college, there was a prophet. We’ll call him Marc Mason. Now I know some of you think these prophet guys are a joke or worse. I’m not going to get into that here except to say that he was as legit as they come. He didn’t ever make silly predictions ala Chuck Pierce, and that’s a very good thing. He had an uncanny knack for speaking words of encouragement and admonition in such a way that it was hard to ignore: Like it was God speaking and not just the words of a friend or the preaching of a pastor.

Anyway, I got to hang out with Mr. Mason a few times. I remember helping him repair the fence in his back yard. I also visited him at work, where he administered databases, something which I didn’t realize at the time that would later become my career. People had always told me that Marc was really different in person than he appeared giving bold prophecies at church. Man, was it ever true. I was amazed at how, well, weak he seemed at so many things. He was no handy man. I was used to the mechanical skills and insight of my father. His kids were around and he didn’t have a grip on parenting them. His teenage daughter was largely in a state of rebellion. He himself was timid in speech. He would stutter frequently, but more often would not say anything at all.

Merton talks about different stages in the life of prayer:

So too there is another stage in our prayer, when consolation gives place to fear. It is a place of darkness and anguish and of conversion: for here a great change takes place in our spirit. All our love for God appears to us to have been full of imperfection, as indeed it has. We begin to doubt that we have ever loved Him. With shame and sorrow we find that our love was full of complacency, and that although we thought ourselves modest, we overflowed with conceit. We were to sure of ourselves, not afraid of illusion, not afraid to be recognized be other men as men of prayer.

-Thomas Merton, No Man is an Island, p.48

Marc was more a man of prayer than anyone I knew, yet he himself was very uncomfortable being known AS a man of prayer. I questioned him at length about prophecy and how he thought he ended up with that particular gift. He felt in his prayer time that things would come to him to say. But he felt so stupid saying them. He said he would practice in front of the mirror in the bathroom – trying to put into words what he thought he was hearing in prayer. The less he thought about it the better it went. He was the last person in the room inclined to get up and speak about ANYTHING, but he felt compelled by the holy spirit to somehow say SOMETHING of what he was hearing in prayer.

I think the Lord continually kept him humble along with this. He was to have no claim to fame in himself. In fact, by the traditional elder standards, he was to forever stay unqualified. His wife of 20 years left him about this same time. And yet, I don’t see these things as his fault so much. Yes, they were the result of his own personality weaknesses and sin (just like all my own problems, and yours too). But I think God picked him to speak to in prayer because God always uses what is foolishness to the world to confound the wise. Even the wise who know their bible so well. I can hear people saying right now: “Bah! This guy couldn’t take care of his own family. Why should I listen to anything he says? Pardon me while I get back to me Jonathan Edwards commentary.” Exactly. But if you heard him speak, you would find yourself listening regardless. They are not his own words. Merton tried to get at what this communication may feel like:

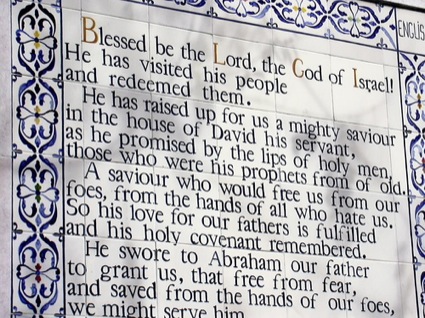

Finally, the purest prayer is something on which it is impossible to reflect until after it is over. And when the grace has gone we no longer seek to reflect on it, because we realize that it belongs to another order of things, and that it will be in some sense debased by our reflecting on it. Such prayer desires no witness, even the winess of our own souls. It seeks to keep itself entirely hidden in God. The experience remains in our spirit like a wound, like a scar that will not heal. But we do no reflect upon it. This living wound may become a source of knowledge, if we are to instruct others in the ways of prayer; or else it may become a bar and an obstacle to knowledge, if we are to instruct others in the ways of prayer; or else it may become a bar and an obstacle to knowledge, a seal of silence set upon the soul, closing the way to words and thoughts, so that we can say nothing of it to other men. For the way is left open to God alone. This is like the door spoken of by Ezechiel, which shall remain closed because the King is enthroned within. (p.50)