To contrast with all my posts lately about the psychological and social problems related to intangible work, I present this passage from The Mythical Man Month, by Frederick Brooks. Brooks is with me in that one of his favorite books of all time happens to be The Mind of the Maker, by Dorothy Sayers. He certainly draws on some of those ideas here.

When I find myself enjoying programming (or remembering why I got into it in the first place back when I was just a kid), these sorts of things are what come to the surface.

The Joys of the Craft

Why is programming fun? What delights may its practitioner expect as his reward?

First is the sheer joy of making things. As the child delights in his mud pie, so the adult enjoys building things, especially things of his own design. I think this delight must be an image of God’s delight in making things, a delight shown in the distinctness and newness of each leaf and each snowflake.

Second is the pleasure of making things that are useful to other people. Deep within, we want others to use our work and to find it helpful. In this respect the programming system is not essentially different from the child’s first clay pencil holder “for Daddy’s office.”

Third is the fascination of fashioning complex puzzle-like objects of interlocking moving parts and watching them work in subtle cycles, playing out the consequences of principles built in from the beginning. The programmed computer has all the fascination of the pinball machine or the jukebox mechanism, carried to the ultimate.

Fourth is the joy of always learning, which springs from the non-repairing nature of the task. In one way or another the problem is ever new, and its solver learns something: sometimes practical, sometimes theoretical, and sometimes both.

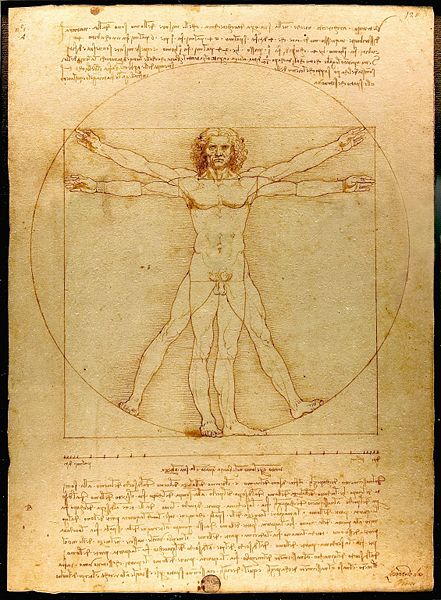

Finally, there is the delight of working in such a tractable medium. The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought-stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by exertion of the imagination. Few media of creation are so flexible, so easy to polish and rework, so readily capable of realizing grand conceptual structures. (As we shall see later, this very tractability has its own problems.)

Yet the program construct, unlike the poet’s words, is real in the sense that it moves and works, producing visible outputs separate from the construct itself. It prints results, draws pictures, produces sounds, moves arms. The magic of myth and legend has come true in our time. One types the correct incantation on a keyboard, and a display screen comes to life, showing things that never were nor could be.

Programming then is fun because it gratifies creative longings built deep within us and delights sensibilities we have in common with all men.

I shall rephrase his points with a few additional thoughts.

1. It’s fun to make things. My wife just made two six-foot-long benches in the shop behind the house for our dining room table. She had a blast. I have felt the same way about software many times. We make things because God makes things. We are like him in this way first of all.

2. We don’t want to make things in a vacuum. We want to see other people use our things. This is why music HAS to be shared for it to be complete as an art. All artists and craftsmen have a hole in their soul until they witness another human being interacting with or affected by their creation. We don’t just want to make nonsense works – we desire them to be used. Cathedrals are not just beautiful landmarks, but also great places to hold church services. In my own work, I have always gravitated toward producing tools where I can perceive who the immediate users are. I have not, at this point, gotten a lot out of contributing theoretical knowledge or abstract components to open-source projects. I can’t see whatever happens to them. I’m sure my work could help someone out there, but it can be difficult to go through the effort to repackage it in a “sharable” form and then send it into the void. Some people really dig doing this though.

3. We are fascinated by interlocking moving parts that move in cycles. Well, some of us are anyway. This aspect of the making process seems to be largely the domain of the male gender. A friend of mine recently commented that his son loves anything with wheels on it. He probably will his whole life. This is also why I love robots, but don’t like androids. One holds all the fascination of a machine, the other is too much like a twisted human being. For what it’s worth though, Data was still probably the best character on Star Trek.

4. The joy of always learning? I agree completely that there is a joy in learning. I love learning! This blog is little more than an attempt to get a bit more mileage out of my own learning. However, I have not always found myself excited to learn about software development, my discipline. If it will help me solve an immediate problem – yes, but otherwise no. This is why I dropped out of computer science in college. What a drag! I wasn’t learning anything I wanted to know. Everything I wanted to know I could learn on my own online. The same for everything I needed to know to do my job.

The quick and steady cycle of throwing technology in the garbage can and embracing the next new thing every couple of years was (and is) ultimately wearisome to me. I just can’t get excited about the newest version of (fill in the blank). I can get excited about learning new techniques when I have a goal in mind. I would dive into GPU controller code up to my neck in a second if I was motivated to write a cool 3D game. But if someone gave me a job documenting hundreds of pages of the same GPU code and paid me a salary to do it – somebody shoot me. This point needs a bit more nuance.

5. The medium of working on a computer is so flexible! You can create entire worlds, “castles in the air, from air” and design every aspect of how they function.

If you have ever played any of the old Myst video games, you know that the stories involve a family of people who possess a special magic for creating new worlds from scratch by writing books. Their writing craft is not easy though and the characters often lament the instability of the places they create. Some of the worlds are very dangerous to visit in the game because the laws of physics just aren’t working right. The good guys in the game try to create beautiful places for people the live. The evil ones want to make their own worlds and then lord over them likes gods. They both express frustration at the perilousness of their craft. There is a tension between their desire to settle down and have a family, like ordinary people, and their desire to keep experimenting with their creative writing magic.

A similar profession mentioned a few times in the Star Trek universe is the craft of writing Holodeck programs and characters. It’s considered to be rather difficult to do well, as evidenced by the terrible results when some amateur characters on the show take a stab at it themselves. The parallel with writing software is even closer here.

We want to create worlds, just like God, but we can’t fathom how God thinks about things, really. So we have to imagine some sort of in-between material, a language of mediation. For the writers of the Myst books, it was written words on the page – careful descriptions mixed with spells. For the Holodeck programmer or the contemporary software developer, it is some sort of programming language – a special language for describing things and casting our own spells of sorts.

Just as it was easy for the Myst authors to get lost in their work and go crazy, it was a great temptation for Holodeck authors (and users) to become addicted to their creations and their creative processes and be lost and disconnected from their friends and reality too. In the same way, when we bury ourselves too deep in our creation, then we are divided from friends, family, and community. It isn’t healthy. We need these connections to remain intact to remain whole ourselves. They are the things that really matter. To the degree that we can do this today, then technology is no evil. Let us learn wisdom and self-restraint.