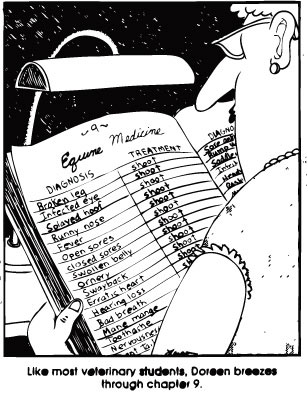

Well I’ve established (ha! or at least suggested) that a lot of books, especially contemporary religious books, are chock full of cultural critique, but are largely devoid of solutions.

Back to why. Why/how do these books even get written? Why only describe the problem more thoroughly? An academic researcher can probably get away with this, but a lot of these books, most of them in fact, or clearly intended for a popular audience. I am going to try and describe what I think is happening, at least some of the time here.

Most theology and Christian culture writers are minor celebrity pastors. They feel like personally, due to their ordained day job, are sufficiently “doing their part” and serving “more than enough” to be above reproach in their vocation. (Do you need to preach a sermon to Mother Teresa exhorting her to serve more? Nah, she’s got that covered at least.) So from this position of critical safety, they can opine about (quite literally) anything and everything. They can diagnose all day long and not BOTHER to articulate a substantial cure since they, personally, are already maximally involved as part of some sort of cure already (as far as they can tell).

In a vacuum where a well-reasoned cure does not exist or a proposed solution is only vaguely defined, what takes the place? It is filled by the person speaking himself. Whether they (the speaker) are actively seeking to promote themselves is irrelevant. What happens is that the “cure” becomes the replication of the speaker. And the listeners, intellectually agreeing and emotionally resonating with the diagnosis, desire the cure, desire to take part in the cure. And so they find themselves desiring to become like the speaker. People who sit under effective pastors find their legitimate list of vocations to include only being a pastor or something very similar. This is a natural reaction. It happens in the absence of a substantial solution. Not prescribing a concrete cure does not mean that none is communicated. The vacuum will be filled by SOMETHING, probably the speaker’s own person. When we are long on diagnosis and short of cure, then the cure becomes highly personal and imitative.

So what is Wendel Berry’s solution? As far as I can tell it’s “Everyone become a small farmer and learn to be happy being poor, just like me.”

After writing this, I checked to see if there were any discussions regarding Berry on the BHT. It didn’t take long to find exactly what I was looking for.

OK, I guess I have to say something. I’ve been sitting this one out because my best friend is totally into Wendell Berry. I’m a little into Wendell Berry. I think eating local and thinking about community is cool. But my friend is so into it that it drives him to despair. He feels trapped, doomed to participate in an economy he hates and the burden of rage against the machine wears him out. I try to encourage him with eschatology, but it usually doesn’t take.

Why so much stridency on this subject? It seems so out of proportion. …from the little I’ve read of Berry he doesn’t seem as full of anger as his disciples. Anybody want to do a little armchair psychoanalysis of what’s going on here?

And a reply:

…I hate being stuck in an evil system, being part of an economy that promotes poverty, and that I can’t do a damn thing to get out of it. I would LOVE to have my own farm, big enough to sustain my family (in produce and in trade) and some of my close friends. I can’t afford it. I can’t afford to buy all organic, all cruelty free, or all local… and I love in Portland OR, mecca for the ultra green hipsters! I can barley afford to feed my family! If I think about this stuff too much, it will send me to depression… and I can’t afford to go there in any way, shape, or form. Thinking about the kingdom of our God and his Messiah swallowing up this evil, corrupt way we live (all over the world, I’m not talking just USA) is the only thing that gives me any hope.

I really hate to be picking on Wendell Berry (sorry Seth T.!) because he really is a sharp guy, but his work provides such a good example of what I’m talking about here. Berry offers a brilliant critique, but then articulates no cure. So what do his followers pick up as the cure? Be like Berry. So they get themselves a few chickens in their back yard (as much as the city will allow them), stop shopping at Walmart, eat out less and maybe try to get to know their neighbors. But they are frustrated because it seems like so very little in an ocean of waste and consumerism.

When I hear reformed fan boys invoke John Piper’s NAME far more often than his actual ideas, I wonder what is going on. I think that in spiritual matters, even something as systematic as Calvinism can fail to SEEM like a substantial solution to life’s immediate problems. That still involves (and will always involve) the long daily trek of faith.

Here is a counter example involving a local pastor, Doug Wilson, who has written on a lot of different (and sometimes very controversial) topics over the years.

The advocacy for Classical Christian Education is a very substantial, meaty solution to many of the problems presented by modern schooling. That is why the focus of the movement has been on the methodology and (to some degree) the philosophy rather than a particular person. In truth, this advocacy has probably been by far Wilson’s most influential contribution, but because it has been so long on cure, he, the person, is effectively diminished. He isn’t this larger-than-life leader of the movement. In fact, lots of people involved who may even now be teaching Sayer’s revised Trivium in schools across the country don’t even know who he is. That’s good. It keeps everyone’s eye’s on the ball. It also prevents Doug from personally becoming a stumbling block (and he would).

On the flip side again, we can also REJECT the given cure and try to imitate the person instead. Great musicians usually have one piece of advice to their wannabe fans: practice, practice, practice. But instead, we buy the Eric Clapton signature edition guitar, start smoking cigarettes, and even go shopping for the right kind of hat. That’s the stuff we can imitate and it’s easy. We don’t see him practicing four hours straight every morning. We just saw the four-minute clip on MTV.

Girard shows us that, for better or worse, we are always imitating others and imitating their desires too. For ideas to stand on their own, they need to be sufficiently separated or distant from the person presenting them. For discipleship (which is a form of intentional imitation) to be effective, the master and apprentice need to have a common goal strong enough to prevent rivalry with each other. The master musician and his student need to pursue music, not the teacher personally. The pastor and the lay minister need to pursue God, not the reproduction of the pastor. We need to be careful when being long on diagnosis and short on cure. We may think we are doing the world a favor, but maybe not so much. We can guard against this by being humble and minimizing ourselves personally from the solution. Reformed blogger Carl Trueman recently exhorted celebrity pastors to voluntarily NOT go speak at so many big conferences. It’s too bad the reception to his idea has been lukewarm.

“He must increase, I must decrease” said John the Baptist. He’s still right.