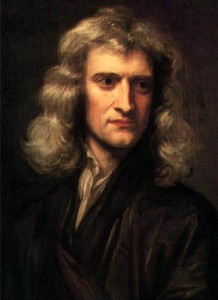

A couple weeks ago, I read a short biography of Isaac Newton by someone calling himself “E.N. da C. Andrade”. A good $1 find at the used bookstore. I scribbled down a few things of misc interest to me.

As a child, Newton apparently built many of the machines he found described in a book called The Mysteries of Art and Nature, by John Bate. The biographer describes it as “a good boy’s book”. This actually looks really cool. It was printed in 1654 and has lots of engravings. You can get a reproduction on Amazon for $20.

It seems to me that making things with your hands leads TO book learning – not the other way around with boys. They need to hit the books later after the hand is established.

—

Newton was not a child prodigy and though his mind was at work on great things in his early twenties, he didn’t publish anything until he was almost 30.

I always like to hear about guys that bloom late ’cause I can be like them too, right? Ralph Vaughn Williams, one of my favorite composers, is in the same boat. He didn’t write anything good until his thirties.

—

After some prodding, his school master convinced Newton’s mother not to force him to become a farmer and instead go to University. He paid his way through by working as a teaching assistant, something that richer students didn’t need to do. This still happens today. How many of us were jealous of our rich classmates that didn’t have to balance study and part-time job to pay the bills? They sucked!

—

While on break from college during the plague (yikes!), he stayed at home for 18 months. He was 23. We must have “accomplished extraordinary things brooding alone”. In fact, the bulk of his future work was just writing down what he figured out during that time.

—

In reading Newton’s Biography, the thrill of the “truly original idea” assaulted me! This passion is reflected in the movie A Beautiful Mind, where Russell Crowe plays the real life John Nash, a brilliant mathematician. This is contra many of his colleagues who simply wanted to look good and score political points in academia by working on mediocre ideas and recycled research. Newton had some of this same contempt for scientific “posers”.

—

I love this quote comparing Newton with John Wallis, another great mathematician.

“Had Newton set out to record his mathematics with the open-handed liberality of a Wallis, who delighted in revealing not only the finished results but all his tricks methods and who taught as he wrote, how different would have been the sequel…” – Mathematician H.W. Turnbull (on p.49)

This is what I’m talkin’ about! I have got to get a teaching job. Seriously.

—

Another good quote, when asked why he built all his own scientific instruments (grinding lenses to make telescopes, etc.)

“If I had stayed for other people to make my tools and things for me I had never made anything of it.”

You definitely find this with computer programmers. If you want something created that doesn’t exist, well, you got to build the dang thing yourself!

—

This passage highlights a key distinction in Newton’s approach to science that was different than nearly all his predecessors.

“You sometimes speak of gravity as essential and inherent to matter. Pray do not ascribe that notion to me; for the cause of gravity is what I do not pretend to now…” People sometimes ask, “What is electricity?” and say that nobody knows. What kind of an answer they expect or have in mind it is hard to guess. Probably if Newton had written on electricity and had been asked this question he would have replied that he did not pretend to know, that he was concerned with how electricity behaved, with the mathematical laws from which you could deduce the measured electrical forces and effects. this attitude of Newton’s is that of modern science, but it was new in his time and was one of the things that people trained in the old philosophy found hard to understand. (p.79)

Newton doesn’t ever try to answer the question “What IS it?” He only sets out to answer “How does it work?”. I think he would be pretty disgruntled with some of the ridiculous conjecture and extrapolation with goes along with contemporary research.

—

The biographer again and again praises a handful of certain scientists who, besides their intelligence, were able to discern between “what does matter and what does not.”

He is observing that academia is full of smart people, but many, if not most of them spend their time and energy pursuing thing things of little to no value. Exactly what his criteria is for what “matters” and “does not matter” is not ever given. I think he is appealing to common sense. You’ll know it when you see it!

—

The author also talks often of Newton’s “correspondence”, that is the letters he exchanged with other thinkers around the world. We don’t use that term much anymore. This seems odd to us today as they are all a phone call or an email away. It makes me wonder though if the formality of a hand-written letter might convey with it a seriousness and sincerity that is lacking from today’s quick emails or “social media” (a phrase I am not fond of). They are so easy to send, it also makes them easier to ignore. I have had been able to email some of my favorite authors and scholars. Some of them have graciously answered my questions later that same day! Others have completely ignored me. Perhaps a physical letter would be “special” enough that it would be harder to ignore? How easy is it to ignore a “poke” on Facebook? Despite the internet, in some ways are we more constrained now than before. Our circles are wider, but our face-to-face circles are often smaller. Our imaginations could stand to grow…and shrink.

—

Amazingly, Newton was not exactly a specialist. His enthusiasm was equally divided between:

1. Exact science

2. Administration of the mint (his well-paying day job)

3. Religious matters (theological studies)

4. Chemistry and alchemy

Very interesting. He didn’t seem to find it necessary to have a job in academia to participate in it. His scientific work was certainly more than a hobby. He still spent a lot of time on it as well as his other studies. He wasn’t married, so he didn’t have a wife and kids to take care of. Still, it wasn’t his actual career. It’s funny that today he would not be qualified to even apply for the job he held as a public administrator. He would need a pointless MBA for that. By all accounts though, he was very good at running the mint.

—

Newton was a Christian and an Anglican, but he quietly denied the 39 articles. Why? He didn’t believe the doctrine of the trinity – such a common hang-up for intellectual types. It continues to make me wonder how necessary it is to the core of the creed. I believe in it myself for certain and I know that disbelief in it has far-reaching negative implications. Still, it seems that it’s a confusing enough theological topic that having an unorthodox belief about it should not immediately make your practice of Christianity illegitimate. The Syrian church was a significant Christian presence for centuries and they were Nestorians, not proper Trinitarians. Today, the Oneness Pentecostals are still undeniably Christian as well, despite the fact that they would get a low score on certain parts of the theology quiz. Still, at the end of the day it seems like a pretty important thing to have in the creed, though I can sympathize with those who get hung up on it.

—

The author suspects that the greatest scientists are able to intuitively figure things out and then start their experiments and proofs in close to the right direction from the beginning. They are not simply exploring haphazardly. They have a secret compass or sorts.

It is possibly true that all very great men of science have a power of, as it were, smelling out the truth, divining what is behind scientific appearances: they do not argue things out to begin with in the nice, clean, tidy manner in which in which they afterwards present their findings to the world. Newton, perhaps, possessed this power of scientific foresight, correct scientific surmise, to a greater extent than any other man. (p.128)

Equivalent in the arts I think is a musician-composer who begins with an improvisation and only later sets out to write it down and orchestrate it. Pierre Bensusan has stated explicitly that this is how he composes. I think that’s probably what Bach did for everything too. He wrote at the keyboard, not at his desk, using the organ as an instrument to be transcribed, not as a tool to assist in his writing. There is a big difference between the two.