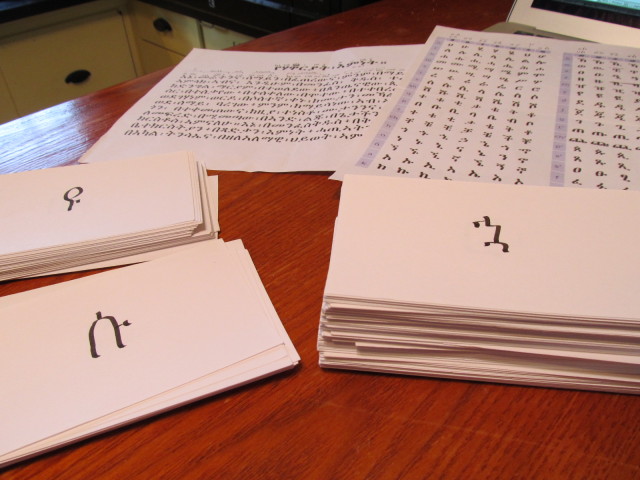

Well, I decided to bite the bullet and learn the Ge’ez script. The amount of Amharic material available transliterated into Latin is almost zero so if I’m going to learn anything beyond the ~400 words my wife and I studied last year, I must get a handle on the alphabet. It’s over 250 unique syllabic characters. They follow a nice pattern… except when they don’t which is a good 30% of the time. Fortunately, my wife made a full stack of nice flash cards for me by hand to practice with! They are working great so far.

Will dust praise you?

A bit of psalm 30 with some commentary:

To you, O LORD, I cry,

and to the Lord I plead for mercy:

“What profit is there in my death,

if I go down to the pit?

Will the dust praise you?

Will it tell of your faithfulness?

(Psalm 30:8-9 ESV)

The language of his appeal to God takes us right back to the thematic foreground of language: there is no point in God’s allowing him to die, because lifeless dust cannot praise Him, cannot report to others His “truth” or “faithful performance”, one instance of which would be now to save the supplicant.[!]

It is through language that God must be approached, must be reminded that since His greatness needs language in order to be made known to men, He cannot dispense with the living user of language for the consummation of that end.

The essential condition of active articulation [of words] that distinguishes all of us above the Pit from those who have gone down into it.

-Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry, p.135

This may explain why ghosts (if they are indeed real in any sort of non-demonic sense) seem to virtually never be able to speak, outside of literary fiction. At best they can just bump around. They may even be seen to some degree, but they cannot articulate language.

In other news though, “Will dust praise you?” The psalmist thinks not and implores God not to let him be turned to dust. But Jesus offers some interesting push back to this:

As he was drawing near—already on the way down the Mount of Olives—the whole multitude of his disciples began to rejoice and praise God with a loud voice for all the mighty works that they had seen, saying, “Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord! Peace in heaven and glory in the highest!” And some of the Pharisees in the crowd said to him, “Teacher, rebuke your disciples.” He answered, “I tell you, if these were silent, the very stones would cry out.”

(Luke 19:37-40 ESV)

Will dust praise you? Dust is just finely crushed up rocks. Same thing. Will the rocks praise God? Dang right they will! It’s better for man to do so, but if he doesn’t, even the dust knows that Jesus is walking by. Even the realm of death is swallowed up by Him.

The sower will overtake the reaper

The imagery in Amos 9 about the restoration of Israel takes on an eschatological tint due to it’s hyperbole.

“Behold, the days are coming,” declares the LORD,

“when the plowman shall overtake the reaper

and the treader of grapes him who sows the seed;

the mountains shall drip sweet wine,

and all the hills shall flow with it.

(Amos 9:13 ESV)

The plowman will overtake the reaper because the latter will have so much grain to harvest, while the treader of grapes will scarcely have time to complete the vintage before he finds by his side the eager sowers of a new crop. This does not quite cancel out the curse in Genesis of earning bread by the seat of one’s brow, but it does intimate a smooth and rapid current of fertile production that recuperates through joyful labor something of the Edenic experience.

-Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Poetry, p.156

Are things really THIS good when Israel comes back from captivity in 5th century B.C? Sounds to me more like a time reserved for the rule of Christ on the earth. Notice they are still tilling the earth, not sitting on clouds playing harps.

The Just king of psalm 72

In psalm 72, Solomon writes of the coming just king. But the nature of his empire unusual.

Give the king your justice, O God,

and your righteousness to the royal son!

May he judge your people with righteousness,

and your poor with justice!

Let the mountains bear prosperity for the people,

and the hills, in righteousness!

May he defend the cause of the poor of the people,

give deliverance to the children of the needy,

and crush the oppressor!

May they fear you while the sun endures,

and as long as the moon, throughout all generations!

May he be like rain that falls on the mown grass,

like showers that water the earth!

In his days may the righteous flourish,

and peace abound, till the moon be no more!

May he have dominion from sea to sea,

and from the River to the ends of the earth!

May desert tribes bow down before him,

and his enemies lick the dust!

May the kings of Tarshish and of the coastlands

render him tribute;

may the kings of Sheba and Seba

bring gifts!

May all kings fall down before him,

all nations serve him!

For he delivers the needy when he calls,

the poor and him who has no helper.

He has pity on the weak and the needy,

and saves the lives of the needy.

From oppression and violence he redeems their life,

and precious is their blood in his sight.

Long may he live;

may gold of Sheba be given to him!

May prayer be made for him continually,

and blessings invoked for him all the day!

May there be abundance of grain in the land;

on the tops of the mountains may it wave;

may its fruit be like Lebanon;

and may people blossom in the cities

like the grass of the field!

May his name endure forever,

his fame continue as long as the sun!

May people be blessed in him,

all nations call him blessed!

Blessed be the LORD, the God of Israel,

who alone does wondrous things.

Blessed be his glorious name forever;

may the whole earth be filled with his glory!

Amen and Amen!

The prayers of David, the son of Jesse, are ended.

(Psalm 72 ESV)

Robert Alter comments thus:

The ideal king will rule from sea to sea, but even the verb of dominion, ‘yerd’, is qualified by its punning ocho of ‘yered’, the verb describing the ruler’s “descent” like rain on grass. The kings of all the earth, from Sheba and Saba in the south to westward Tarshish and the islands of the Mediterranean, do in fact prostrate themselves before the just monarch, but there is no indication in the poem of how he has managed to seize power over them. Indeed, the only verb of aggression he governs is “to crush” in line 4, an activity directed against the oppressors of the poor, and continued in the kings’s compassionate acts of rescue int he progressively heightened four versets of lines 13-14. The poem tactfully implies, without explicitly stating, a causal link between the beneficent effect of the just king indicated in lines 6-7 and the subsequent vision of imperial dominion. It is as though all the rulers of the earth will spontaneously subject themselves to this king, lay tribute at his feet, because of his perfect justice.

-The Art of Biblical Poetry, p.132

I love this. I think I love the psalm even more now. The future rule of Christ will not be like the others empires we have experienced on earth. I think sometimes we imagine that it WILL be like the other ones. This passage in Philippians gets mentioned a lot:

Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven and on earth and under the earth, and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

(Philippians 2:9-11 ESV)

I have often been told that every knee shall bow. Some of us will choose to bow and others will get their heads pressed down to the ground by a heavy divine boot. But in this psalm, the king is SO good, the nations spontaneously subject themselves to him. There is no talk of him conquering them with a sword and breaking their will. Granted, this still leaves room for stubborn rebels, but the normal state of things is rejoicing at the establishing of his empire and the removal of the old government. THIS ruler is finally just and the only crushing he does is of oppressors of the poor. An incomplete picture to be sure (he rides in on a white horse at some point), but I think this should be the dominant picture of the earthly rule of King Jesus. Can’t wait!

Misc notes on Robert Alter’s The Art of Biblical Poetry

Excerpts I found the most interesting, with a bit of description. Overall I found the book a challenging read. I had to have at least two cups of coffee beforehand to tackle it. It was worth it though – learned a lot. His earlier work The Art of Biblical Narrative is going to naturally be more useful though since most of the OT is in prose. I would definitely recommend it before this one.

—

We have different expectations of poetry from the get-go.

“As soon as we perceive that a verbal sequence has a sustained rhythm, that it is formally structured according to a continuously operating principle of organization, we know that we are in the presence of poetry and we respond to it accordingly…expecting certain effects from it and not others, granting certain conventions to it and not others.” – Barbara Herrnstein Smith

Quoted on p.6

—

A great quote about artists here. I agree.

Let me spell out the general principle involved. Every literary tradition converts the formal limitations of its own medium into an occasion for artistic expression: the artist, in fact, might be defined as a person who thrives on realizing new possibilities within formal limitations.

p.24

—

The Hebrew imagination was unabashedly anthropomorphic but by no means foolishly literalist.

p.36

Some folks criticize the bible for being so anthropomorphic so often (“Come on, God doesn’t really have hands!”) but I don’t see any problem with it at all. It’s an effective way to communicate to us humans. Just don’t take it too serious.

—

Here, Alter takes aim at post-modern philosophers who think they can detect brilliant post-modern philosophy in the mind of the psalmist. On the contrary, they believe very much in the power of language and in God hearing it an understanding.

I do not want to propose, in the manner of one fashionable school of contemporary criticism, that we should uncover in the text a covert or unwitting reversal of its own hierarchical oppositions; or more specifically, that silence is affirmed and then abandoned in consequence of the poet’s intuition that all speech is a lie masquerading as truth because of the inevitably arbitrary junction between signifier and signified, language and reality. On the contrary, the ancient Hebrew literary imagination reverts again and again to a bedrock assumption about the efficacy of speech, cosmogonically demonstrated by the Lord (in Genesis 1) Who is emulated by man. In our poem [Psalm 39], the speaker’s final plea that God hear his cry presupposes the efficacy of speech, the truth-telling power with which language has been used to expose the supplicant’s plight. The rapid swings between oppositions in the poem are dictated not by an epistemological quandary but by a psychological dialectic in the speaker.

p.70

—

An interesting comment on the practice of head-shaving for mourning. It shows up in the psalms, but is actually forbidden.

Dressing in sackcloth and saving the head are both ancient Near Eastern mourning practices, but the latter may be more shocking to the sensibilities, both because it is an act performed on the body, not just a change of garment, and because it is a pagan custom actually forbidden by Mosaic law. The last point illustrates how the conservatism of poetic formulation, sometimes reflecting no-longer-current practices or beliefs, might be exploited for expressive effect.

p.74

—

A common theme in Alter’s commentary is that the poetry IS largely the content. It’s not just a technique the author is using to embellish what he really wants to say but actually what he really wants to say.

What I am suggesting is that the exploration of the problem of theodicy in the Book of Job and the “answer” it proposes cannot be separated from the poetic vehicle of the book and that one misses the real intent by reading the text, as has too often been done, as a paraphrasable philosophic argument merely embellished or made more arresting by poetic devices.

p.76

The choice of the poetic medium for the Job poet, or for Isaiah, or for the psalmist, was not merely a matter of giving weight and verbal dignity to a preconceived message but of uncovering or discovering meanings through the resources of poetry.

p.205

Tolkien disliked allegory but loved poetry. I think he must have seen the latter as a legitimate medium and the former as an artificial container or embellishment of sorts. Just a theory.

—

In the ancient Near East a “book” remained for a long time a relatively open structure, so that later writers might seek to amplify or highlight the meaning of certain of the original emphases.

p.91

This makes post-editing and additions not an evil thing like it is today. We are so used to treating books as high self-contained units. Publishing and copyright laws make it extremely so. But in ancient times, these things would float around and run on and be passed down through generations of scribes, copied occasionally. That what we have in the Old Testament is a curated collection of writings that a later editor put together should come as no surprise. We need not be bothered by that thought, as if it makes the bible less magical. That’s the only way ANYTHING got written down back then. It’s not like writing and disseminating things are now.

—

Here, Alter deals with the issue of Behemoth and Leviathan in Job. Growing up in young-earth-creationist circles, these passages were always pulled out as some sort of proof that dinosaurs and humans romped around together in recent history. I’m afraid I find the sort of explanation given below much more convincing.

To put this question in historical perspective, the very distinction we as moderns make between mythology and zoology would not have been so clear-cut for the ancient imagination. The Job poet and his audience, after all, lived in an era before zoos, and exotic beasts like the ones described in Chapters 40-41 were not part of an easily accessible and observable reality. The borderlines, then, between fabled report, immemorial myth, and natural history would tend to blur, and the poet creatively exploits this blur in his climactic evocation of the two amphibious beasts that are at once part of the natural world and beyond it.

p.107

—

Some great thoughts on the necessity of language with regards to religious experience.

But God manifests Himself to man in part through language, and necessarily His deeds are made known by any one man to others, and perhaps also by any one man to himself, chiefly through the mediation of language. Psalms, more than any other group of biblical poems, brings to the fore this consciousness of the linguistic medium of religious experience. These ancient makers of devotional and celebratory poems were keenly aware that poetry is the most complex ordering of language, and perhaps also the most demanding. Within the formal limits of a poem the poet can take advantage of the emphatic repetitions dictated by the particular prosadic system, the symmetries and antitheses and internal echoes intensified by a closed verbal structure, the fine intertwinings of sound and image and reported act, the modulated shifts in grammatical voice and object of address, to give coherence and authority to his perceptions of the world. The psalmsist’s delight in the suppleness and serendipities of poetic form is not a distraction from the spiritual seriousness of the poems but his chief means of realizing his spiritual vision, and it is one source of the power these poems continue to have not only to excite our imaginations but also to engage our lives.

p.136

—

On how the natural vagueness of poetry has made large parts of the bible still very meaningful to readers today and not just to their initial audience:

If we could actually hear God talking, making His will manifest in words of the Hebrew language, what would He sound like? Since poetry is our best human model of intricately rich communication, not only solemn, weighty, and forceful but also densely woven with complex internal connections, meanings, and implications, it makes sese that divine speech should be represented as poetry.

Such speech is directed to the concrete situation of a historical audience, but the form of the speech exhibits the historical indeterminancy of the language of poetry, which helps explain why these discoures have touched the lives of millions of readers far removed in time, space and political predicament from the small groups of ancient Hebrews against whom Hosea, Isaiah, Jeremiach, ad their confreres originally inveighed.

p.141

—

On of the best teachers I had in college was always saying, “Be specific, use examples.” Here, Alter rewrites Isaiah 49:14-23 as prose and then describes what was lost in the transition. Go good example indeed.

But Zion said, “The LORD has forsaken me;

my Lord has forgotten me.”

“Can a woman forget her nursing child,

that she should have no compassion on the son of her womb?

Even these may forget,

yet I will not forget you.

Behold, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands;

your walls are continually before me.

Your builders make haste;

your destroyers and those who laid you waste go out from you.

Lift up your eyes around and see;

they all gather, they come to you.

As I live, declares the LORD,

you shall put them all on as an ornament;

you shall bind them on as a bride does.

“Surely your waste and your desolate places

and your devastated land—

surely now you will be too narrow for your inhabitants,

and those who swallowed you up will be far away.

The children of your bereavement

will yet say in your ears:

‘The place is too narrow for me;

make room for me to dwell in.’

Then you will say in your heart:

‘Who has borne me these?

I was bereaved and barren,

exiled and put away,

but who has brought up these?

Behold, I was left alone;

from where have these come?’”

Thus says the Lord GOD:

“Behold, I will lift up my hand to the nations,

and raise my signal to the peoples;

and they shall bring your sons in their arms,

and your daughters shall be carried on their shoulders.

Kings shall be your foster fathers,

and their queens your nursing mothers.

With their faces to the ground they shall bow down to you,

and lick the dust of your feet.

Then you will know that I am the LORD;

those who wait for me shall not be put to shame.”

(Isaiah 49:14-23 ESV)

Paraphrased into prose:

Days are coming, the Lord declares, when your exiled children, whose strength was afflicted on the way, and whose ankles were put in chains, will return in exultation to Zion. And your oppressors will flee from your midst, and your people will inherit their land and build its ruined cities, and plant fields and vineyards in place of the desolation. And I will cause them to dwell on their soil, for My loving care will not depart from them On the day when I return their captivity, nations will bring them tribute, and none will make them afraid.

…and the analysis:

What has been left out of the prose version is the symbolic presence of Zion as a despereate, suffering woman, and the manifestation through God’s dialogue with Zion of the Lord’s tender, unfaltering love for Israel. The biological immediacy of womb and breast and bosom that contributes to the emotional force of the poem is also absent from the prose. Left out as will is the sense of miraculous surprise in the return to Zion when the breeaved woman suddenly discovers that her children are alive and well, that the ver regents of the earth now cradle and care for them.

p.161

—

According to Alter, Proverbs 1:5-6 warns us that having a wise text isn’t good enough. You have to know how to read it.

The transmission of wisdom depends on an adeptness at literary formulation, and the reception of wisdom by an audience of the “wise” and the “discerning” – requires and answering finesse in reading the poems with discrimination, “to understand proverb and epigram.” The proem [preamble] of the Book of Proverbs, in other words, at once puts us on guard as interpreters and suggests that if we are not good readers we will not get the point of the sayings of the wise.

p.168

—

On how the Bible writers weren’t trying to make a name for themselves or go for originality and novelty – the opposite in fact.

The Bible knows nothing of the personal lyric; the anonymity of all but prophetic poetry in the Bible is an authentic reflection of its fundamentally collective nature. I of course don’t mean to suggest that poetic composition in ancient Israel was a group activity only that the finished composition was meant to address the needs and concerns of the group, and was most commonly fashioned out of traditional materials and according to familiar conventional patterns that made it readily usable by the group for liturgical or celebratory or educational purposes. The orientation toward collective expression also explains the formal conservatism of biblical poetry.

p.207

—

A disclaimer of sorts, found on the very last page:

We cannot all be poets, but what some are privileged to grasp through an act of imaginative penetration others may accomplish more prosaically step by step through patient analysis.

p.214

—–

Less is more – amplifying meaning through reduced vocabulary

Thought he doesn’t connect these ideas specifically in his book, I was struck by several passages in Robert Alter’s The Art of Biblical Poetry where the power of the text is manifest through the relative smallness of Hebrew vocabulary and grammar.

Studying Ethiopian Amharic lately made me much more aware of this. For example, in English we have the words “stick”, “cane”, “staff”, and “club”. Look up any of these in Amharic and you get the same single noun: “dula”. Hebrew, being a Semitic language like Amharic shares many of its traits.

In discussing various biblical poetic passages, Alter draws attention to how the author uses the vagueness of the words he has at his disposal to great effect. This is light-years away from English, where we have by far the most vast dictionary of any civilization in history – stealing words from everyone and incorporating them into our lexicon. On the one hand, this makes English the most potent and flexible of all mediums for poetry but it also PREVENTS it from working the sort of magic that is sometimes going on in scripture. This doesn’t work so well with an audience that expects more exactitude.

Here are a few notable examples of what I’m talking about:

—

In Jeremiah 4, the Hebrews are warned that the land will be made desolate. The word for “land” is ‘eretz, which is also the word for “earth”. So is the prophet talking about something small and local or grand and eschatological? Perhaps both at the same time.

By contagion, the land is not dissociated from all the earth, and the desolation that will overtake it is a terrifying rehearsal of the utter end of the created world. Thus, the very attachment to hyperbole and the intensifying momentum of the poetic medium project the prophet’s vision onto a second plane of signification.

p.155

—

For then I would have lain down and been quiet;

I would have slept; then I would have been at rest,

with kings and counselors of the earth

who rebuilt ruins for themselves,

or with princes who had gold,

who filled their houses with silver.

(Job 3:13-15)

Our English translation is actually quite a bit more exact than the original. The translators made a lot of decisions about the meaning.

Kings and counselors rebuild ruins in the cycle of creation and destruction that is the life of men – or perhaps, since Hebrew has no “re” prefix, the phrase even suggests, more strikingly, that what they build at the very moment of completion is to be thought of as already turning into ruins.

p.81

Do you rebuild ruins or BUILD ruins? In Hebrew – it’s the same thing. The irony is preserved.

—

A false balance is abomination to the Lord: but a just weight is his delight.

(Proverbs 11:1 KJV)

Alter describes this passage from proverbs as being more “disturbing” in the original. I have to agree.

“Two kinds of weights, two kinds of measures” [in other translations] (literally, “weight and weight, measure and measure”). God’s decisively negative judgment against crooked business practices is paramount in both versions, but the riddle form makes it possible for us to apprehend more immediately the disturbing contradiction inherent in double standards, weight and weight, measure and measure.

p.178

Misc notes on de Lubac’s Paradoxes of Faith

I had a few other excerpts from Henri de Lubac’s Paradoxes of Faith that I liked. I was tired though and didn’t want to write individual blog posts for them though so here they are in scrapbook format.

—

Advice to all young writers of memoirs and of various forms of philosophy at the very least. It is most of all advice to myself.

All serious thought is modest. It has no hesitation in going to school and staying there a long time. It is by dint of impersonality that it makes a conquest of itself and, without seeking to do so, becomes personal.

p.112

—

This passage makes me think of the public mania over brain scan imagery and how the “neuro” prefix has been attached to nearly everything lately to try and lend an argument some sort of illusionary legitimacy.

We do not know what man is, or rather, we forget. The farther we go in studying him, the greater our loss of knowledge of him. We study him like an animal or alike a machine. We see in him merely an object, odder than all the others. We are bewitched by physiology, psychology, sociology, and all their appendages.

Are we wrong, then, to pursue these branches of learning? Certainly not. Are the results bogus, then, or negligible? No. The fault lies not with them, but with ourselves, who know neither how to assign them their place nor how to judge them. We believe, without thinking, that the “scientific” study of man can, at least by right, be universal and exhaustive. So it has the same deceptive – and deadly – result as the mania of introspection or the search for a static sincerity. The farther it goes, the more fearful it becomes. It eats into man, disintegrates and destroys him.

p.119

—

Any authority is necessarily a teacher. It is only because we are still en route and our future state is not yet unfolded that, int eh voice of God our Father, we come to discern the Master commanding us and so have a strict feeling of obligation. It is for the same reason that there is a hierarchical authority in the Church. When God will be whole in everyone, in the Church Triumphant, the City of the Elect, there will no longer be any other hierarchy than that of charity.

Authority is ultimately based on charity, and its raison d’etre is education. The exercise of it, in the hands of those who hold any part of it whatever, should then be understood as pedagogy.

p.26

I’m actually still trying to make sense of this. Not sure if it’s profound or not!

—-

We do not want a mysterious God. Neither do we want a God who is Some One. Nothing is more feared than this mystery God who is Some One. We would rather not be some one ourselves, than meet that Some One!

p.214

Scary!

—

Professors of religion are always liable to transform Christianity into a religion of professors. The Church is not a school.

p.224

This makes sense coming from someone from a liturgical and sacramental tradition. Protestantism, on the other hand, has been dominated by the giant mondo teaching sermon. Honestly, I still very much enjoy the latter when done well, but I am less convinced that it’s place is in a worship gathering, rather than a school of sorts.

—

The passion of wanting to reform everything in the Church is for the most part in inverse proportion to the supernatural life; that is the reason why authentic and beneficial reforms almost never begin with such passion.

p.231

More argument for the slow burn of reform versus the mess of revolution.

—

“How can I present Christianity, you say?” – There is only one answer: as you see it.

“How can I present Christ?” – As you love him.

“How can I talk of faith?” – According to what it is for you.

There is in questions of this sort, when they encroach too far, not a positive duplicity, no doubt, but at least artifice, a lack of sincerity; because there is a lack of faith.p.215

I wish someone would have given me this line a lot more in all those evangelism training sessions I went to while in college.

—

Christianity, it is said, owes this, that and the other to Judaism. It has borrowed this, that and the other from Hellenism. Or from Essenism. Everything in it is mortgaged from birth…

Are people naive enough to believe, before making a detailed study, that the supernatural excludes the possession of any earthly roots and any human origin? So they open their eyes and thereby shut them to what is essential, or, to put it better, to everything: which has Christianity borrowed Jesus Christ? Now, in Jesus Christ, “all things are made new”.p.215

Fan-flippin’-tastic. The secularist says our roots are all in man. The literalist fundamentalist says they are all in God – as if the bible were penned by men in a trance. But we have roots of both kinds. Naturally.

Slow-burn salvation

Many people always see only the disadvantages of the present state of affairs and only the advantages of the one that ought to replace it. What is more, they think that all you have to do is destroy what exists and The Ideal will at once arise from its ruins – and they don’t give a thought to how this might occur. Anyone who shows himself ready to offer practical help to the present reality, with all its defects, is defamed for supporting injustice, for opposing the kingdom of justice.

-Henri de Lubac, Paradoxes of Faith, p.167

Revolution often seen as the way forward instead of reform to our modern eyes. (“Let’s ditch this lame church institution and cook up our own awesomeness!”) or in foreign policy (“Let’s undermine that dictator and install a democracy in that country. That will fix everything!”) There are a ton of examples in the past century, decade, or even in the past year that have been disasters. Our model of disposable materialism even supports this. You don’t ever repair your iPhone when it dies – you get a new one of course. Same with clothes that wear out. An old world tailor is a reformer. Cheap retail textiles from east Asia offer us an endless stream of clothing revolution.

But this is not the wise way, which always seems to demand some kind of heavy patience. It is not God’s way either.

What is the answer to _____ (fill in the blank) problem of the world? The answer, once again, is some kind of slow burn. Some people denounce the Bible for not denouncing slavery proper at the first opportunity. Shouldn’t there be something about in on about the 2nd page of Acts? But the seeds that grew into freedom were all there – they just needed to be watered and they were.

What we see in scripture is a patient progression. God saves his people in time – sometimes a really LONG time. What happened to all those individuals in the meantime? They didn’t see the day of the Lord, but they were still part of the salvation. They had to be. The prophets were holy men, but they didn’t get to see it.

For verily I say unto you, That many prophets and righteous men have desired to see those things which ye see, and have not seen them; and to hear those things which ye hear, and have not heard them. (Matthew 13:17)

Some of them died in exile in Babylon. But were they not still part of God’s salvation? Of course they were. They still count even though they passed out of the story before the last page.

WE in fact are not on the last page either, even if the climax has already occurred. It doesn’t seem too hard to extend Jesus’s parable of the laborers in the vineyard (Matthew 20:1-16) to this “slow burn salvation” as well. The people there from the beginning AND the latecomers both got paid full wages! So we are rewarded for being faithful, even if when we pass from this life, everything is still seems to be a big mess. Our part in the story was still played and it wasn’t trivial.

The resurrection is like a big full-cast Bollywood dance number played while the credits role. Everyone who died is back in the chorus with the surviving hero from the last scene. They may not have even known each other in life, but they all know the same steps now.

Text versus commentary

This is a fantastic passage with regards to the study of scripture and one of my favorite passage from de Lubac’s book.

When we are faced with a very great text, a very profound one, never can we maintain that eh interpretation we give of it – even if it is very accurate, the most accurate, if need be, the only accurate one – coincides exactly with its author’s thought.

The fact is, the text and the interpretation are not of the same order; they do not develop at the same level, and therefore they cannot overlay one another. The former expresses spontaneous, synthetic, “prospective”, in some fasion, creative knowledge. The latter, which is a commentary, is of the reflective and analytical order.

In a sense, the commentary, if it at all penetrating, always goes FARTHER than the text, since it makes what it finds there explicit; and if it does not in fact go father, it is of no use, since no light would then be shed by it on the text. But in another and more important sense, the text, bits concrete richness, always overflows the commentary, and never does the commentary dispense us from going back to the text. There is virtually infinity in it.

-Paradoxes of Faith, Henri de Lubac, p.109

Our ideas grow old with us

Our ideas grow old with us, that is why we pay no particular attention to them, and we are quite astonished at younger minds not falling in love with them in their turn, as we did.

-Paradoxes of Faith, Henri de Lubac, p.98

Why do our our ideas grow old? The answer I think is that they are utterly wrapped up in context and more context. The context changes: we grow old, nations come and go, technology shifts, culture changes, and the rich meaning of our ideas is obscured. We deceive ourselves if we think we deal completely in “timeless truths”, the way a mathematician deals with pure numbers. Even the very words we use to express our ideas reveal the century, even decade, and geography in which they were forged, among other things.

If we really desire to pass our best ideas on, we could do better than to just write them down cleverly in books. This puts (though we or our contemporaries or editors cannot perceive it) a great burden on the reader years later to figure out what the heck we were trying to say. We need to teach our children and grandchildren how to decode them and adapt them. This means being a teacher and ideally, a father.