I absolutely love it when the “forth wall” is broken between enemies in the course of art, or especially everyday life. Some think it perverse when considered theologically, but I am absolutely thrilled and cheered by the notion of tragedy being interrupted by the actors taking off their masks (up until that point you forgot they were actors) and dancing or chatting together like old friends. I love it when movies or plays end with a dance number and the villain comes out and is stomping and spinning to the music next to everyone else.

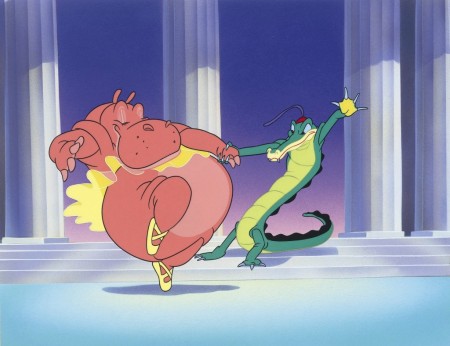

Theologian James Alison likes this idea too and in one of his essays uses the example of the Hippo and Alligator dance from Disney’s old Fantasia animated film. At one point the hippo is surrounded by the evil alligators and seems to be in deadly peril. For just a moment though, she looks up at the camera and gives the audience a wink. It may look like all is lost, but you don’t know the whole story. The player does though. They trust the script writer.

The Super Mario video game franchise gets a lot of mileage out of this idea. One minute, Mario and Bowser are trying to kill each other. On Monday, Mario is roasted alive by fireballs. On Tuesday Bowser is pushed into a sea of lava. On Wednesday they are back, racing go karts and playing tennis together. Video games are a trifling diversion. What could they possibly teach us about the real hard world outside? I think they can help us imagine, just a little bit, what it is like when death is not the end. Death seems so final now, but in the Kingdom of God it is but a distant memory. What is good practice for not taking the scary too seriously today? Perhaps this.

The famous Christmas Truce between English and German soldiers on the front lines in 1914 is an excellent real-life example of this. For a few hours, they put down their machine guns and shared cigarettes and sang hymns. The next day, they went back to slaughtering each other, but with the recognition that all of this was happening as part of some much larger story – one they couldn’t seem to escape, it’s true, and so they pressed on with their part. But it takes real humility to do that – and not taking yourself too seriously. In fact, at the point of loving embrace of the enemy, you are not taking yourself seriously at all.

Another example came up in a photo essay published by the New York Times this week. The author visited a prison in Argentina where the felons enthusiastically practice and play rugby. The program has been praised by some for seemingly helping to rehabilitate the prisoners and keep them psychologically healthy. Once every three months, they get to travel outside the prison and play a full game on a real field against another team. This was my favorite part: Who makes up the opposition? Local lawyers, guards, and even a couple of judges. Classic. The law is as hard as stone but we as creative (not just created) beings are are also gifted with the strange ability to step right outside it, at least for a moment.

“Do you mean to tell me that the rape of that little girl I saw reported on the news last night is just in a script God wrote for his own amusement? Are we all just pawns on the chessboard of some sick game? The devil is just an actor backed up by an extensive cosmic make-up department? We are just robots playing our part? So there isn’t real good or evil? The horror of war is just some kind of bad joke?”

No. Emphatically no. These are the sorts of questions asked by people who cannot trust the author. On a bad day, I ask these sorts of questions too. (The fact that a handful of Calvinists jump to answer “yes” to some of these questions posed above doesn’t help either.) In chapter 13:15, Job says, “Though he slay me, yet will I trust him.” This is coming from someone who really did trust the author, despite his lack of understanding. The reason you can trust him is that He is the kind of author who doesn’t leave his people in the ground. He is the kind of author who raises the dead. And he even sent himself to be the prototype for this resurrection. No-one can fathom how all of this is supposed to work or especially why. You don’t need to. Learn to trust the author. He is arranging for the victory over death to be total. We are walking somewhere in the second half of the story book.