The usual accounts of ‘scientific’ method focus (with good reason, in my view) on hypothesis and verification/falsification. We make a hypothesis about what is true, and we go about verifying or falsifying it by further experimentations. But how do we arrive at hypotheses, and what counts as verification or falsification? On the positivistic model, hypotheses are constructed out of the sense-data received, and then go in search of more sense-evidence which will either confirm, modify or destroy the hypotheses thus created.

I suggest that this is misleading. It is very unlikely that one could construct a good working hypotheses out of sense-data alone, and in fact no reflective thinker in any field imagines that this is the case. One needs a larger framework on which to draw, a larger set of STORIES about things that are likely to happen in the world. There must always be a leap, made by the imagination that has been attuned sympathetically to the subject-matter, from the (in principal) random observation of phenomena to the hypotheses of a pattern.

Equally, verification happens not so much by observing random sense-data to see whether they fit with the hypothesis, but by devising means, precisely on the basis of the larger stories (including the hypothesis itself), to ask specific questions about specific aspects of the hypotheses. But this presses the question: in what way do the large stories and the specific data arrive at a ‘fit’? In order to examine this we must look closer at stories themselves.

-N.T. Wright, “Knowledge: Problems and Varieties”, from The New Testament and the People of God, p.37

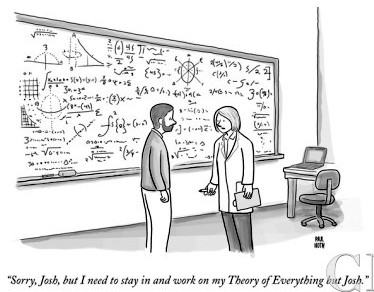

Good science requires imagination, not just good tools and accurate observation. Science also happens inside of these larger frameworks, the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and about the world. Which is why a scientist who shuns philosophy and psychology will be eaten alive by them in course of his own efforts. Our hypothesis don’t happen in a vacuum. We need that air to breathe.