This is a bit of follow-up to my earlier post, Is missionary work really harder now than it was in the middle ages? I could use a variety of examples from history, both ancient and even some relatively recent revivals or foreign mission success stories. However, for the sake of convenience, I’ll use the conversion of the fierce Picts in Scotland to Christianity by St. Columcille’s monks in the sixth century versus attempts to plant churches or strengthen Christian cultural institutions in the present-day secular modern United States.

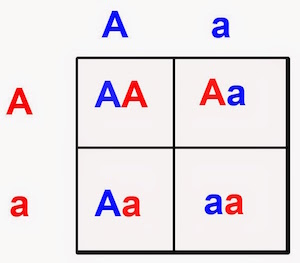

Each of of the questions I’m going to ask can be viewed as having two variables. One could draw a 2×2 grid of four possible logical answers to the question and then evaluate each one. Along the way, I think we’ll find that some options can be eliminated easily, while others are cause for rigorous debate.

—–

1. Were the pagan Picts much more set in their sinful ways or is it our modern culture that is particularly hostile?

A. The Picts were really hard nuts to crack and so are the secularists in our culture today.

B. The Picts were really hard nuts to crack but our current secularists are actually a lot less resistant than they were. People now are much more open.

C. The Picts were actually surprisingly receptive pagans, unlike our extremely cynical and self-confident secularists today.

D. The Picts were actually pretty receptive pagans, and our current crop of pagans are not much different. We’re just whiners.

It’s a toss up as to rather I hear option B or C articulated by Christian leaders most of the time.

—–

2. The conversion of Ireland and Scotland was dramatically successful. Were the old pagans really receptive to the light of Christ, or were the old saints particularly special and amazing in their holiness and methods?

A. The old pagans were especially receptive and the Celtic saints weren’t anything special. Accounts of both are overblown.

B. The old pagans were really, really bad, but the Celtic saints were freakin’ amazing!

C. The old pagans were really, really bad, and the Celtic saints were kind of lame, but the Holy Spirit caused widespread miracles to happen regardless.

D. The old pagans were especially receptive, and the Celtic saints were really great too.

It’s hip and cynical to vote for option A on this one, but I still hear option B from people that like to hype things up.

—–

3. We seem to be having a lot of trouble spreading the gospel. Is it because we suck, or have we just been given an especially difficult task?

A. We suck at perpetuating the gospel, and our culture is really especially resistant to it. Bummer.

B. We do a decent job of communicating the gospel, but the culture is really especially resistant to it. It’s mostly their fault.

C. We suck at communicating the gospel, and the culture is about as receptive or not as any people group has ever been. It’s mostly our fault.

D. We are really good at communicating the gospel, and some in the culture are actually receiving it. It just LOOKS like they aren’t because current elites hate on Christianity in a very public way. That is, we are mistaken in our evaluation of the situation.

The Reformed typically tell a story that sounds like option B (our preaching kicks ass but they aren’t listening), and the Anabaptists and some left-leaning folks talk like option C is what is going on (we’re asleep at the wheel so we can’t blame them too much). Folks like Philip Jenkins, Lamin Sanneh, and some Chinese folks talk like option D is what is going on as soon as you step out of USA/Europe. I’d really like to believe them, but I’m still not sure at this point.

—–

4. Are we anything like the old saints?

A. The old Celtic saints were surely amazing, and actually, we are really spiritual and clever and hard-working too.

B. The old Celtic saints were amazing, but we’re a bunch of losers who play with our smart phones all day and wonder why nothing happens.

C. The old Celtic saints were nothing special, and actually we’ve come a long way since then. We’re way smarter and more theologically orthodox too.

D. The old Celtic saints were not that great, and neither are we. We both suck. Their success was kind of a fluke based on the weird circumstances surrounding the collapse of the Roman Empire.

As a young man, I heard a LOT of option B. I know a lot of my Reformed friends have too. Jim Elliot bios, Charismatic hagiographies of folks like Smith Wigglesworth, “Don’t Waste Your Life”, “Do Hard Things”, etc. I occasionally hear option C suggested, though it’s rarely put front and center.

—–

And one more, getting as close to the bone as possible.

5. How was the Holy Spirit at work in the past and today?

A. The Holy Spirit was doing stuff back then, but not now. Maybe he’s gearing up to burn the world with fire!

B. The Holy Spirit wasn’t really moving back then, but he is now. What happened back then was syncretistic nominalistic crap, but now we’re part of the new Remnant awesome!

C. The Holy Spirit wasn’t really moving back then, and he’s not now either. We’re just tossed on the waves by (probably meaningless) forces we can never understand.

D. The Holy Spirit was doing stuff back then, and he is now too. The wind swirls but has never stopped. We are not alone – not even a little bit.

I’ve heard A and B spoken of by quite a variety of figures. It’s really kind of funny how either of these can be worked into widely disparate theological frameworks. Option C is the default for secular nihilists. I’m for option D.