My wife wrote some more good thoughts on the theology of disability today here. Worth checking out as this topic is definitely a neglected one.

Poem: Why He is worthy

When we exhale we breath out carbon dioxide

When He exhales He breathes out all the elements

His tongue like the heart of a star

When we open our eyes we take in a narrow band of light

When He opens his eyes they were already open

Seeing everything ever before or after – even dark things

When we think we follow only one frustrated line of thought and desire

When he thinks his ideas become fully real

Before the ink is dry on the page

When we love, it promptly grows weary, cold and twisted

When He loves, the universe expands in all directions

New stars by the minute engulf our crooked ways in warmth

The dialectic of modernity in Christian mission

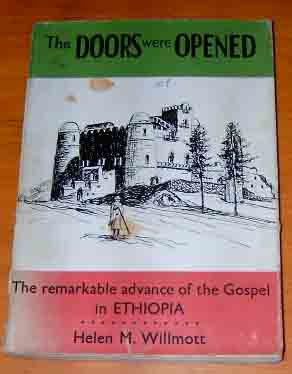

On several passes through the library, I missed this book titled “Marxist Modern” because I didn’t think it had anything to do with Ethiopia, much less the topic I’m most interested in: the development of Christianity there. But then I found it referenced in a bibliography of an article I enjoyed on the topic, so I decided to pick it up on my next pass.

The subtitle of the book is “An Ethnographic History of the Ethiopian Revolution”. The author writes in a detached style in language that does not condemn communism per se, but that nevertheless acknowledges many of the atrocities that were committed during the Ethiopian socialist revolution of the 1970s and 80s. Unlike a lot of accounts, one does not get the impression that the author is denouncing Marxism, but simply telling a story about how its implementation came to pass (and ultimately fail), especially in the rural areas.

Does this all sound very interesting? It’s not really. But smack in the middle of the book is a chapter titled “The Dialectic of Modernity in a North American Christian Mission” and this one really got me thinking.

In it, the author, Donald Donham, tells the story of the Sudan Interior Mission (SIM), the largest and most influential outside Christian organization to make inroads into the country during the 20th century. There were other missionaries there too, but they had only a handful of people. A local woman I know here in town grew up in southern Ethiopia where her parents worked for the SIM.

The SIM was founded in 1897 by the Canadian Rowland Victor Bingham. For Bingham, the “Sudan” was a blanket reference to all of sub-saharan Africa. The organization would go on to send a lot of people to Africa, mostly to Sudan, Nigeria, and Ethiopia, where it arrived in 1927. From the beginning, the organization was not tied to a particular denominations and its missionaries, aid workers, and teachers came from all different protestant backgrounds.

In Ethiopia though, it discovered the already established Ethiopian Orthodox church. It was not welcomed by the Coptic leaders, but rather told to pack up and leave. Early on in their stay however, one of the SIM missionaries, Dr. Thomas Lambie, was awoken in the middle of the night and called to help the local governor of Wellegga where they were staying. He was in great pain and the doctor was able to, using a special pair of tweasers, remove a bug that had crawled into the governor’s ear while he was sleeping. Lambie didn’t think much of it, but his influential patient so raved about the doctor that he was given an audience with Halie Salasie not long after.

The Emperor was absolutely feverish to bring in modern western teachers and especially doctors and wasn’t about to turn down this possibility. The SIM was allowed to “do their Christian missionary thing” in the country, as long as they kept to the rural areas where the Orthodox church had almost no presence (mostly the south), and as long as they established LOTS of hospitals and new schools. At first, this sounded great, but it later became to be a strain on the evangelists. Whenever they wanted to move into a new territory or village, they were told they needed to bring in a bunch more doctors first. Just planting a church wasn’t an option, but only a reward of sorts for various degrees of modernization that the SIM could bring to the country. Lambie, now in charge of operations in the country, played this political game well. He had Ford automobiles imported to the capital (which had only a couple hundred cars at the time) as well as tractors and other modern equipment. He pushed forward with plans to evangelize more unreached rural areas while assuring financial backers back in the US and Canada that the emperor was a legitimate Christian, despite his adherence to (as far as they could tell) a largely alien religion.

Over the years, this whole setup began to have some strange and unintended side-effects. At this point I had better quote from the chapter a bit.

In the conversion process that slowly unfolded, the negative sign of anti-modernism was switched again and again. Consider for example the Biblicism that the missionaries brought to southern Ethiopia, their emphasis on the Bible as the “inerrant” word of God. To North Americans, this doctrine protected religion from the modernist claims of science: whatever science profess to know, all that anyone really needed to know was the Bile: “[The SIM missionaries] felt duty-bound to have a Bible text for every religious statement they made. They believed that their interpretations of the Bible was that held by Jesus and his apostles; they believed in an authoritative Bible and took it with them to southern Ethiopia.

In the context of southern Ethiopia, however an emphasis on the Book had entirely different consequences than in North America. In Ethiopia, being able to read the Bible (and hence other books) in a society in which no one else could separated one, not from modernity – far from it – but from tradition. In the 1930s, the SIM was allowed to use local vernaculars, but after the Italian occupation had ended, it was required to use the national language, Amharic, both in preaching and in Bible translation. For southerners, being literate in Amharic opened a whole new world on the nation, courts, newspapers, radio – in short, modernity.

Another example of this process of inversion occurred in missionaries’ notion of exactly what constituted conversion. Becoming a Christian, for fundamentalists, did not depend upon a mere rite like baptism; rather, conversion required a wholesale “separation” from the world and a basic behavioral change in converts’ moral lives. In North America, this kind of separation meant detachment from tobacco, alcohol, and other sin and, more broadly, from all forms of (modernist) attempts to dilute religious traditionalism [such as modern psychology, Darwinism, materialism, etc.]. But in souther Ethiopia, an emphasis on so-called separation led to a radical rejection of tradition, one that, as one missionary put it, would eventually “blast apart” customary assumptions.

-p.96

The message delivered to the people was not one just of the Gospel of Jesus, but was very tightly tied to free modern medical care, learning to read, and exposure to a whole truckload of other western ideas. Some regions in the rural south went from having an almost zero literacy rate to having some of the highest rates in the country thanks to the schools founded by the missionaries. These people then moved to the city, leaving the family farm in the dust and hoping to make a better richer life for themselves. Sometimes they remained in their new faith, but they frequently abandoned it for a large helping of worldliness. Donham goes on to trace how many of the most enthusiastic supporters of the communist revolution were the young Christians from the south. They used their new-found education not to read the Bible, but to overthrow the Amharas – their ancient overlords and oppressors.

Along the same lines, people also flocked to the missionary stations for modern medical care and took only a feigned interest in the preaching. This is to be expected of course and there is a sense in which Christians must always be willing to give freely even when there is nothing to be had in return. Still, the way it was set up, these things were experienced in such tandem that they could not be separated in the minds of the new converts. Many of them did not even realize until far later that their new faith had anything in common with the religion practiced by the highlanders in the north, their ancient enemies.

What was this “Dialectic of Modernity” that the missionaries are grappling with? It was the contradictory nature of much of their thought and practices. Back at home, the Christians of the SIM and their supporters were actively anti-modernist. They tried to keep traditions alive and respect the past in the face of rapidly changing secular ideas. They tried to preserve things like prayer in public schools, acknowledgement of God in the public square, no legal basis for easy divorce. They placed a high value on community life and family ties. They praised farming and field work and had strong followings in the rural midwest and the south. They decried the rat-race of the city and considered it a damaging moral influence. In short, they were very conservative in just about every sense of the word.

But here they were in Africa being radically progressive! They shunned tradition, encouraging the people to throw away anything remotely connected to the paganism of their past, be it charm bracelets, or various food rituals, or even their language. Before, a couple’s honeymoon would last several months. Now it was encouraged to be only a week so they could go back to working hard, just like industrious westerners. Following Jesus meant it was time to ditch your family if they didn’t want to come along and that was OK because you were a liberal free agent now. Lets hurry up and teach all these goat herders how to read so they can learn, not just about how their sins are forgiven, but about democracy, fertilizers, engines, and biochemistry.

It’s like one minute they were denouncing the evils of Rock and Roll, and then the next minute teaching children to play the electric guitar. How do you keep this tension in your personal philosophy? (By not facing it I suspect. It’s how we handle our own cognitive dissonance today).

How ironic that the leading Ethiopian modernist of the 1920s, ras Teferi, came to support the activities of the arch anti-modernist Sudan Interior Mission. Or was it? For Hingham, the dialectic between anti-modernism and its shadow, modernism, was always more than a simple opposition. These two stances toward the world seemed in fact to depend upon one another and at times to feed into one another.

-p.87

A phrase I often here from people that discuss evangelism, is “What you win with WITH is what you win them TO.” If you “attract” people with cool music, inspirational speaking and good parties, then you have to keep that stuff going or your “ecclesia”, your community, falls apart. Sure, there is some stuff about Jesus in there, maybe a lot of it actually, but it wasn’t a naked gospel that got them in the door, but rather a thickly clothed one. In the same way, when things like modern pharmaceuticals, books, and exciting foreign friends are part of the presentation, they also gain the convert’s allegiance along with what is taught from the Bible. It can’t help but be this way. Faith matures over time and can (and does!) overcome these entanglements, but that can take years and for some people never seems to occur.

I want to stop for a moment and say that, despite what I may be recounting above, I am not highly critical of the SIM missionaries. I am actually really impressed with some parts of their story. They did, in my opinion, a TON of things right. They were very serious about establishing indigenous churches. They trained local native pastors and got out of the way very quickly. They didn’t prop up new churches with a single dime of foreign money but made sure they were self-sustaining from the first day. They made sure it was all locals on the elder boards. One day they (the white folk) would be serving communion, and as soon as they had a few people baptized, the next week, they had THEM serve it. Great stuff. And the church exploded in their six years of absence after the Italians kicked them out of the country in 1936. This sort of “give them Jesus and get out of the way” attitude is bold, courageous, and dramatically more sustainable than some other models. For all the secular modern baggage the missionaries may have unwittingly brought with them, they still took some huge steps in decoupling their own western culture from the gospel and enabling the new churches to flourish. I dig that.

And I dig where I see that happening today, even in our own backyard, ecclesia semper reformanda. And I also am troubled by the dialectic of modernity as it continues today. I frequently have difficulty reconciling the two in my own life. One antidote is to remember that _____ (fill in the blank) will NOT save you. Christ has saved you.

Is Africa mysterious?

I’m going to have to say ‘Yes’. Let me explain.

A few days ago, Leithart briefly summarized an essay on language by Charles Taylor’s here. In it, he defines “mystery” in this way:

Taylor suggests there are three facets to mystery: (1) It refers to something we cannot explain; (2) it refers to something that we cannot explain that also is “something of great depth and moment”; and (3), since “mystery” etymologically refers also to “the process of initiation, in which secrets are revealed,” a mystery is something we cannot understand so long as we take “a disengaged stance” to it, something that must be explored by immersion.

I’ve been searching for things on the web since the early nineties when I dialed in on a 9600 baud modem and used the Lynx text-browser and Alta Vista. I know how to find stuff online. I know how to find scholarly journals and rare works on WorldCat and order them up through my (seemingly unlimited!) access to the inter-library loan system. I’ve frankly, never had trouble finding more than enough information before about whatever I desired to know about. The challenge was always picking what to read from a vast ocean of options.

Now I have found myself in a far different and (shockingly) uncharted place. The past 18 months, I have spent most of my reading and personal research on the topic of life and Christianity in Africa, especially Ethiopia. I’ve scoured the library. I’ve hit Google a thousand times. I’ve dug through old and new journals. I’ve read blogs, I’ve read travelogues, I’ve looked for answers all over the place and I’ve come up with… not a heck of a lot.

“a mystery is something we cannot understand so long as we take “a disengaged stance” to it, something that must be explored by immersion.”

I seriously considered giving up several times and turning my attention elsewhere but the very fact that this topic has been difficult to study seemed to suggest that there are things of value buried here that few others have ever bothered to touch. So I’ve responded by diving in deeper and also casting a wider net. I’ve had to put away popular books and just focus on first-hand research, most of it published only in obscure journals and often poorly written. I’ve corresponded with several people living and serving in the country and tried to kindly ask for the straight dope. I’ve had the fortune of speaking with a local women who spent her childhood there, the daughter of missionaries in the south. I’ve exchanged emails with a pastor there as well as another man who operates an orphanage. I’ve learned to read more scraps of the language.

As I poke around I feel like I’ve just barely scratched the surface. At the same time, I am beginning to realize that I’ve already put together more pieces on this particular topic than, well, all but a tiny handful of people. I have friends writing their theses on some theological topic or trying to tease out one more tidbit on Augustine. Everywhere they turn, somebody seems to be so much smarter or well read. I find the same. I want to write something on a passage of scripture and I read some commentaries and conclude that I’m a moron. I want to develop a topic that Girard touched on and discover about 20 other people more qualified to write on it than I. I know that I have something valuable to contribute, but it can be stifling to be surround by so many smart guys writing really good material. Not so with this particular aspect of Africa. Everywhere I turn now, I’m surrounded by people that don’t have a clue. Or if they do, they only have experience with one small part of the picture I’m trying to cover. There is nobody to explain the picture to me. I’m having to dig it up a tiny piece at a time.

I stumbled upon this cool piece of music yesterday and its exemplary of the kind of difficulties I’m facing on this project. I actually heard this on the radio in the middle of the night. This song (music video below), is from Tukuleur, a French-speaking Senegalese hip-hop group. Its a cover (sort of) of the 1981 song ‘Africa’ by the band Toto. Pretty cool. It showed up on a world music compilation CD a few years ago. I’d love to hear some more of their stuff. Can you find it on iTunes? No. Surely you can buy their album on Amazon. Never heard of ’em. They look kind of interesting; I’ll go read the Wikipedia article on the band. Ha! Good luck. Oh! I know, I’ll check the French Wikipedia. Nice try. Nope. Library loan can surely find it for me. Here it is. Oh, the only copy of their album is non-circulating in a library in Lyon, France. Google… practically nothing. What about the usually rich AllMusic? Nothing.

Start using your ears. I swear I hear (uncredited) Mah Damba, the griot singer from Mali on the interlude after the chorus. Who knows? I finally found a stray copy for sale on eBay. The title proclaims “RARE!!!”. They’re not kidding. I am informed that a lot of pop music in Ethiopia is still only available on cassette tape.

(Do yourself a favor and listen to this – even if you don’t like rap one bit.)

That’s how I feel about nearly everything I’ve tried to learn about Ethiopia. This liturgy book is used by literally millions of people. Is there an English translation? No. This guy could help me. Does he have an email address? Of course not. This map is way out of date. This book is full of communist propaganda from the 1980s and not helpful. This book has all the same tourist crap in the last one did. This author was right there in the thick of it, but only wrote down some boring things about politics. Arg. Huge gaps abound.

People think Africa isn’t mysterious anymore since the entire Congo jungle is on Google Maps. Not so. To discover almost anything that actually matters still requires immersion, as far as I can tell. And (warning!) when you are immersed, YOU change and the questions you asked before turn out to be the wrong questions.

Alphabetic nuance

In learning Ehtiopian Amharic, I’ve been puzzled and confused by the host of redundant alphabet characters. Many of the consonants have exactly the same phonetic sound and I cannot discern any reason why sometimes one is used and not another. None of the language sources I have explain how they are used either. Sure, they say WHY there are redundant characters in the collection of 268 – they are remnants left-over from different peoples and dialects dating back to the time before Christ. As Ge’ez script developed, many of these minor variations were combined and codified, but some of the duplicates remained. OK. Great. Whatever. But that still doesn’t tell me anything about how they should be used or read.

That is why, a few days ago, I was delighted to find then this passage in the memoir Notes from the Hyena’s Belly, by Ethiopain expatriate Nega Mezlekia.

Once Memerae [teacher] was completely satisfied that we could identify each of the characters, he taught us why certain of the letters repeated themselves. There were sixty-three such characters. For instance, there were six characters representing Ha, two for Se, four for …

Because it was rude to associate a king with something so intimate as a kiss, the ki in king would be different than the ki in kiss. As the sun was a symbol of power and eternity, the su in sun would be different from the su in sugar, which was a perishable item. And as power was something for the gods and kings, the po in power… We spent the rest of the year learning to identify celestial and imperial features, and to distinguish their spelling from that of everyday things. No individual would be accorded a learned status who lacked the ability to recognize such subtle differences.

-p.33

Well it’s clear that I’m a hecka long way from being “accorded a learned status”. Fortunately these subtleties are not so detectable in spoken conversations.

Realizing this got me thinking though how this is another very subtle way that Amharic uses different tools to achieve a variance of meaning. In English we have a gigantic vocabulary, but many of these African languages have to make due with only a fifth or a tenth as many words. How do they still have a rich literary tradition? Through tricks like this. In English we use the same 26 characters for everything. Poets sometimes try to play with capital letter placement and line breaks to provide a shade of meaning, but that only goes so far. Here though, you actually have phonetic characters that carry their own baggage, be it celestial or earthly, beautiful or plain, common or rare. The skilled writer can use these to great effect – if his audience knows their history and convention. It’s another great feature that doesn’t translate well at all.

Respect the lion

Abdi earned his living smuggling humans out of the country and bringing in contraband goods from the neighboring countries of Djibouti and Somalia. Once, when he was traveling with his fellow smugglers through the desolate mountains, one of his friends looked up and saw a lion sitting on a bare rock, casually watching the nomads. The lion was perfectly disguised, blending in with the greyish rocks and dying grass and it was a matter of chance that the smuggler noticed him.

Instead of heeding what his ancestors had drilled into him and leaving the lion alone, the man raised his rifle, aimed clearly at the beast and fired. he missed. The lion disappeared. No one though much of this little incident until hours later, when they were crossing a narrow alley. They were walking in single file along the belt of the treacherous mountain when a tortured shriek was heard from the end of the line. Looking bac, they saw one of their men disappear downhill, carried by a lion. They could not tell if it was the same lion they had encountered earlier but there was no mistaking the identity of the victim – the man who had shot the rifle and missed. The moral of the story is that lions do not eat peace-loving nomads. If you are a nomad and you find yourself in the belly of a lion, rest assured – you are not nearly so peace-loving as you thought.

-Nega Mezlekia, Notes from the Hyena’s Belly, p.164

On an attempt to fix modernism with more modernism

I just finished reading Punished by Rewards by education writer Alfie Kohn. My wife informs me that this book was all the rage in education programs at the university during the mid-1990s. I was asked to read it as part of a book discussion group and figured I should write down a few thoughts. This is a book review of sorts, though it is an opportunity to talk about some larger issues.

First of all, I’ve been spoiled by reading so much N.T. Wright, David Bently Hart, C.S. Lewis and other people that are careful writers and thinkers and who define their words up front. In contrast, THIS book was full of mushy thinking, self-undermining arguments and a disingenuous use of language. Chief among these was the use of the term “reward”, of which the title refers. At various points the word is used to refer to golden stars handed out to elementary students, candy used as bribes for good behavior, all academic grades in general, salary and money paid for work of any kind, verbal praise, lighter punishments, intangible situations in the afterlife and sometimes something as general as any reciprocal social interaction or exchange. Again and again the context changed but the thing being critiqued was supposed to somehow, in the abstract, be mostly the same thing and treated as such with few qualifications.

That’s not to say all the ideas presented in the book are terrible. Some of them seem pretty sound, but it was a very mixed bag. I felt that at the end it mostly served to muddy the waters. I thought he book was going to be long on diagnosis, short on cure, but to his credit, Kohn really does have three fairly substantial chapters of suggestions at the end of the work. The problem is that almost none of them are likely to work – ironically, for the same reasons what he is critiquing doesn’t work. At the end of the day, the author is firmly stuck in the land of Modernism. He correctly identifies problems caused by Modernism, but all he has in his belt are the same old tools used to dig us in the hole in the first place. He has no answers but more of the same in a different form. I’ll get into some specifics in a bit.

The first chapter is a critique of B.F. Skinner’s behaviorist psychology and its dehumanizing effects. I was cheering enthusiastically through all of this. Wendel Berry would have approved.

Freedom is just another word for something left to learn: it is the way we refer to the ever-diminishing set of phenomena for which science has yet to specify the causes.

p.6, Summarizing B.F. Skinner’s definition of “freedom”

It was refreshing to hear a secularist critique scientism. I was optimistic at this point.

It is no accident that behaviorism is the [United States’] major contribution to the field of psychology, or that the only philosophical movement native to the U.S. is pragmatism. We are a nation that prefers acting to thinking, and practice to theory; we are suspicious of intellectuals, worshipful of technology, and fixated on the bottom line. We define ourselves by numbers – take-home pay and cholesterol counts, percentiles (how much does your baby weight?) and standardized test scores (how much does your child know?). By contrast, we are uneasy with intangibles and unscientific abstractions such as a sense of well-being or an intrinsic motivation to learn.

p.10

Things start to go south though in chapter two where he quotes a passage from Luke (the only scripture reference in the book) and reveals to even the half-witted reader than he has absolutely no grasp on the nature of the gospel. From there the talk runs the gamut of topics from Karma to Marx. With regards to parenting, he is always saying, “Ask the child, ask the child, ask the child.” I wanted to shout, “DUDE! They don’t know! Congratulations – you get to tell them.”

Lots of things we to today are terrible. Like what? Grades are bad, they are a distraction from actual learning. Spanking is bad it just causes resentment. Rewards are bad, they numb the receiver to real passion for the subject. Financial incentives are bad because then people won’t love what they do but only the money that comes from it. Bonuses are bad because they create bad vibes among coworkers. Bribes are unethical (where do these ethics come from anyway?). Competition is bad as it makes kids fight each other. Annual job evals are worthless because only regular continuous feedback is helpful. Giving people outside incentives is manipulation and therefore immoral because… just because.

And how does the author back up all these claims? “Recent research”, “Recent research”, “recent research”. This phrase appears literally hundreds of times throughout this book. It is used to justify virtually every assertion the author makes. Doing X is bad. Why? Recent research. Doing Y is good! Why? Recent research. Why did the chicken cross the road? Recent research. Good grief. Again, no sense of history, no imagination for pre-modern man, etc. The bibliography is practically wall-to-wall psych research from the 1970s. He seems ignorant of virtually all other disciplines as well as the last couple thousand years of human history. Aristotle had some really good things to say about education you know. But screw that, let’s just quote John Dewey some more. Bleh.

At the same time, some of his criticism was right on.

Standardized tests stifle and suffocate the best teachers – the ones who are innovative and creative – while doing little to reform the bad and lazy ones.

Stack ranking has been proven to be an absolutely terrible way to manage employees. A expose on the decline of Microsoft during the past decade found that every single ex-employee interviewed decried the practice as utterly insane. Once a year, every person in a unit (usually about a dozen people) were ranked in order from 1 to 10. Whoever was number 1 got a big raise and whoever was number 10 got fired, no matter what. It didn’t matter if the whole team was great and the number 10 guy was actually pretty good – he got fired. Or if the whole team was mediocre – it didn’t matter, the top guy still got a huge promotion regardless. Totally stupid right? But this went on for years and years with many people absolutely swearing it was a good idea. My friends tell me that schools in Korea do this too. From what I can tell, Ethiopian schools are the same.

Grades really do distract from the joy of learning, but they are only one element of an entire curriculum that, when applied to a large group, is going to forge ahead leaving some people in the dust and others bored on the sideline. Just about every page I read I found myself thinking, “Gee, homeschooling would automatically fix that, and that, and that.” I still think so.

At one point, Kohn talks about how he gave a lecture on all of this at a prestigious prep school. Unbeknownst to him at the time, the students had just finished a week of exams and were in the middle of applying for colleges, many of them trying to get into Harvard. Their applications were packed with extracurricular activities and club participation that was there solely to look good to the admission board – not because they cared one bit about actual activities. After talking about how grades and achievements and rewards were all not truly worth pursuing, one student stood up and asked, “Well, what else is there?” He admits that he had no answer.

I was actually a bit shocked to find he even recounted this story. He then proceeds to continue on his merry way, suggesting in passing that there is more to life than contrived achievements. But what? What!? He doesn’t have an answer. And that is because he is still trapped in modern materialism. Institutional schooling is all he knows. Hyperspecialization and scientism is the still the fallback. It’s the way he was trained. He knows something is terribly wrong, but can’t put his finger on it since his pointing finger is part of the problem. The truth is, you can’t answer any of these questions with psychology. You need philosophy and, dare I say it, theology.

Later, in one of the practical how-to chapters, he gives several suggestions about how to temper your praise of children. His points? I am not making this up:

1. Don’t praise people, only what they do.

2. Make praise as specific as possible (so again, it can be nailed down to an action or event, not a person)

3. Avoid phoney subjective praise. Evaluate performance objectively. (Yeah. Uh huh. Can anyone actually do this?)

There were some more points, but the first one blew me away. After all that talk about the perils of dehumanizing people, here we are back to being as materialist and pragmatic as possible. He needs to take his own advice from earlier in the book and not treat humans as robots. This sort of contradictory thought is everywhere in the work. I think he’s trying hard, but he just doesn’t have the right tools. His faith in science to reform itself appears unending.

At one point, he says that we need to “Decouple the task from the compensation.” You know, there is actually a word for that. It’s called LOVE.

To learn more about love though, you need to start with the fear of the creator – the one who is love itself. Eliminating competition and grades will do nothing to solve the root of our envy and violence. This is a sacred task that requires the dispensation of a supernatural agent – that of the Lord. All these things are excluded from the academy from the get-go, which is why all they have left is idle talk.

Still, to flip yet again, some of his advice was not bad. What is your child ALREADY engaged in? Start there to teach him new things. We constantly teach by example all day long. Go meta! Explain what you are doing. If you can’t get rid of grades, at least explain why they are in place and take some of the edge off them. Don’t let them remain a powerful mystery symbol. Natural consequences are best – avoid contrived situations.

Oddly enough, one of the best parts of the book was an appendix near the end where he spends about ten pages discussing the difficulties of defining what “intrinsic motivation” really is. He brings up some really good points and shows how the phrase is used in different contexts to mean different things and that when we discuss it we need to be aware of the various pieces of baggage. In my opinion, this sort of thing shouldn’t have been hidden in the back, but made front and center in the thesis of the work. If you are going to talk about something challenging, then call it out up front and do all you can to prevent your readers from getting confused or derailed. Don’t let things get muddy.

I concluded that about 80% of the advice in the book could be recovered if the context were discussed a bit more and an age qualification given. Some of Kohns ideas will only work with young adults, others only with very young children, but he almost never makes a distinction, preferring to treat everyone from babies to people in vocational colleges in the abstract. It doesn’t work. Perhaps in twenty years this author’s work has gotten more refined and nuanced. I hope so. Behaviorism is still in need of some serious push-back today.

I ended up feeling the same way about this book as I did about much of Robert Bly’s Iron John. With that work, you had a secular modernist that couldn’t shake the feeling that something was seriously wrong with modernism. BUT, the only cure he could come up with was more modernism. In Bly’s case, he was forced to admit that something about modern feminism was destructive to men and so he turned to Jung and mythology to try and poetically bolster a masculine ideal. Nice try, but an imagined sacred just doesn’t cut the mustard. You need a real one. The same is true for this book. Using the most recent 20 years of ivory-tower output to trash the 20 years before it only goes so far. It’s like trying to clean up a mess with dirty rags.

The naming of Eve

When you name something, you declare that you own it. You name your children and they take that name and use it and affirm your declaration. You may name your house, or your horse, or your musical instrument as well. You are not just describing the thing in question, but personalizing it, claiming it, connecting it to yourself.

In Genesis 1:27 we see God create man and women. They have no names at this point. In the next chapter, we find that God has named his special single child Adam. In 2:22, the woman is made from Adam’s rib. Adam describes who she is (“She shall be called Woman for she was taken out of Man.”), but she is still nameless at this point. Meanwhile Adam names all the living creatures. The Lord brings them to Adam to see what he will call them. Creation is given to the dominion of the man and the woman. Throughout Genesis 3, Adam is Adam, but the woman is just the woman. Then in verses 16-19, God pronounces his terrible curse on the man and the woman.

The very first thing Adam does in verse 20 after the curse is to name the woman Eve. That is the first occurrence. She is now the possession of Adam. And Eve lets this happens. She loves him, even as she hates him. They are estranged from God and from each other but the connections to both their creator and their spouse are of the impossibly deep kind that can never be loosed. She will always be lonely without him and utterly lonely without her creator. In his flailing and grasping and failing, Adam will reach to create a meaningful existence for himself. He will build cities and empires. He will oppress Eve along the way, but then he will love Eve. He has to.

Naming Eve is a curse that can’t be wholly undone before the fullnes of all redemption. The body is baptized, but it has been owned and cursed with desire after the husband. This needs bodily resurrection to be properly reset.

As I write this I’m listening to a slow and high violin solo. I can’t help but draw things together.

The violinist plays ever so gently the harmonic tone, exactly in the middle of the string. What makes it sound so mysterious? It can’t quite decide if it is the octave below or the one above. It is never wholly the one or the other. Your mind tries to attach to it and file it away, to properly name it. That is what Adam does. He names everything he sees and hears. But when he hears the harmonic, he stops and listens a little longer. Finally, in a distracted fog, missing the next few notes, he gives it a name, but even then he doubts. Perhaps it has another name. Can something be two things at once? Even so, it is like unto himself. He named Eve as an other, but sometimes she is so much Adam, just taking up a slightly different space. His own existence and nature of creation is a mystery. So mysteries like unto his own are just slightly disturbing as they remind him of his own origin and his own incompleteness.

This is why, in the new Jerusalem, we are neither married nor given in marriage. For the redemption of our split of being is not to be found in the wedding of couples. That is a substitution image for now, but when there is no need for the light of the sun or the moon (Revelation 21:23), there will no longer be a need for that union as well. The redemption Chrisy aims to bring does not unify this difference like a “better” marriage, but dissolves it for something entirely better. That is why those who make a great fuss about gender, be it professors of “women’s studies” or patriarchs lording it over their wives and daughters, are not actually participating in the healing of mankind. To emphasize our differences is honest, but it is to live in the past and the present. The love of Christ pushes us into the future, where no daughter is given in marriage. In the same way, women’s societies that revel in their independent professionalism, their desert of equal rights, or even their breast feeding, are asserting things that cannot heal the rift. This is equally true of men on elder boards that fail to listen to their wives. They aren’t healing anything either.

What is the reason that Christ’s ministry on earth not exhibit a sexual element? He is the firstborn of the new creation. He needs no sexual union, no husband-wife relationship, to fully express his humanity. This is extremely telling, is it not? It was not good for Adam to be alone, so then Eve. But the second Adam had no Eve, and yet was not alone. To do the will of his father was his bread and oxygen. When we are raised on last day, we will see him, and when we see him we shall be like him (1 John 3:2). Our union with Christ will supersede our substitute unions to the daughters of Eve in the meantime. Women will be truly free then – free from the name Adam gave to them, free from their desire for him – and able to properly give and receive love from their creator. They will be unbroken. Depression and weakness will be things of the past. The same is true for all the sons of Adam. They will be made new – unbroken and non-depleting. Their ambition for false things will finally dry up for all ages. In the vision in Revelation 3, Christ gives us a new name. Eve gets a new one too, this time not from Adam but from her maker.

(Thanks to Fr. Thomas McKenzie for mentioning the naming of Eve after the curse in a recent lecture. I had not made the connection before. I think this whole line of reasoning could be developed a lot further than I have briefly done here. Why? I am attempting to resolve some of the tension between complementarianism and egalitarianism. I affirm the natural just tuning of the hierarchy while also pushing back and saying it is not an eternal institution but a temporary and fundamentally broken one. To redeem all creation is to gradually see the distinctions blur as both the man and woman are image bearers of the same.)

A couple of poems by Rumi

This is pretty off-topic, but I really enjoyed this NTY interview with Robert Bly (whose work I have mixed feelings about). In it though, he quotes a couple of poems from Rumi translated by Coleman Bark. They were so great I felt the need to copy them down. No this is not a Tumblr blog, but sometimes I do this sort of thing anyway just to keep it filed away somewhere.

Who makes these changes?

I shoot an arrow right.

It lands left.

I ride after a deer and find myself

Chased by a hog.

I plot to get what I want

And end up in prison.

I dig pits to trap others

And fall in.I should be suspicious

Of what I want.

—

I reach for a piece of wood. It turns into a lute.

I do some meanness. It turns out helpful.

I say one must not travel during the holy month.

Then I start out, and wonderful things happen.

Pharmacology

Every night I administer eye drops containing betaxolol hydrochloride, brinzolamide, and the prostaglandin analogue latanoprost to my daughter. What do these marvels of modern medical chemistry accomplish? Almost nothing. That’s right – almost nothing.

Some drugs are simply chemicals that already occur in your body – you just change certain balances by administering them and naturally (more or less) push things in a desired direction. Other drugs cause profound reactions in specific cells. A well-timed antibiotic has saved many a man from near certain death. Pain killers make surgery possible in nearly all cases and daily life possible for many.

But other drugs are just grasping at straws to accomplish anything at all. I was reading a detailed report on how one of the drugs I mentioned above works and discovered that 80% of the drug is recoverable in urine within 17 minutes. 17 minutes!? Do you know what that means? It means as soon as you put the stuff in your body, it says, “What the hell is this? Flush that straight down the toilet!” The affect of the drug is literally felt for just a few minutes. You could administer it more often, but that is challenging, has many ill side-effects and only increases overall effectiveness a tiny amount. And speaking of side-effects, some of them are downright odd. One of them will cause your eye lashes to grow extra long. Another will make a funny taste in your mouth. A third can weaken your breathing – all with a single drop in your eye. So do they do what they are meant to do? Sort of. A little bit, but often nobody knows why. Under the mechanism heading on one prescription, it reads: “Reduces interocular pressure. The precise mechanism of this effect is not known.” Nice.

Now I love learning about this stuff. Some of my best memories are when my father used to read and explain passages from his pharmaceutical reference tome (among other things) to me when I was a young man. My sister is getting her doctorate in the field in a few weeks time. (Congrats!) But the more I interact with these materials first hand, the more I realize that this clever stuff will not save us. Not even close. Our own half-life is not much longer than some of these remedies. The only thing that will save my daughter is love – perfect love. It’s the only thing that will save me too.

God I need your help tonight

Beneath the noise

Below the din

I hear your voice

It’s whispering

In science and in medicine

“I was a stranger

You took me in”The songs are in your eyes

I see them when you smile

I’ve had enough of romantic love

Yeah, I’d give it up, yeah, I’d give it up

For a miracle, miracle drug-Lyrics from “Miracle Drug”, by U2