Everywhere the Gospel goes, everywhere Christianity goes, it encounters existing people and cultures. These established people were shaped by their current religion (the one being supplanted) as well as the kind of work they do, the kind of music they like, how literate they are, and even by things as simple as what they eat or what the weather is like in the region. Their genetics even play a role. Everywhere, Christians take on a certain shade of the surrounding culture. And in general, this is good. Red and Yellow, Black and White, they are previous in his sight, etc. Africans have got to MOVE during worship! Highly education Britons would rather sing 4-part harmony while standing still.

syncretism: The amalgamation or attempted amalgamation of different religions, cultures, or schools of thought.

The church of the first century as described in the New Testament epistles is one divided by geography. Each regional church had absorbed some cultural and folk religious beliefs into it’s culture. This is why the Judaizers (who wanted to keep much of the Levitical law intact) were denounced in one letter and the intellectually elite gnostics in another. Corinth had trouble with long established sexual promiscuity leaking into the congregation. Some were rich, some where poor, some were really poor. No matter how hard beliefs are codified and written down, there will always be significant variation on the ground. Theology affects life and just as often, vice versa.

In Latin America and Africa, the devotion to certain local pagan deities was sometimes morphed into the veneration of the saints. In the worst cases, the Virgin Mary took on side-effects of the regional fertility goddess. In more innocuous cases, the local heroes of the old paganism were canonized and their biographies reinvented. Early Chinese Christians had a Saint Confucius. This made the new church seem a bit more homey and less alien to the locals. Opinions vary among scholars and church leaders as to whether this sort of thing is really terrible or no big deal. That it can be distraction from the core of the Gospel is indisputable though.

This sort of thing happens with all other religions too. I was intrigued to discover that Buddhism in southeast Asia is filled with local folk religious elements – belief in evil spirits, magic amulets, etc. None of these have anything to do with the core beliefs of Buddhism. These sorts of supernatural elements are seen as ridiculous by the more intellectual branches, such as the Zen Buddhism more common in northern China or Japan.

Now we Americans are a Christian nation based on the Bible itself! The founding father’s didn’t have a folk religion! We have a clean theology. Just look at how nice and tidy our confessions are! OK. Not really. So what has American Christianity absorbed? “Rugged American Individualism” – certainly an idea with some positive qualities, but one that can be convincingly traced to a “just me a Jesus” soteriology that is completely unaware of the larger community – even our own children. “The American Dream” of capitalism and opportunity combined with Christianity leads to the prosperity gospel (God wants you to be rich) – a rather unique (and destructive) export from the United States.

The Roman Catholic church modeled it’s authority structure on the Roman government. This seemed to work great for a couple centuries but after the empire’s collapse seemed, in hindsight, like a pretty flawed way to organize the priesthood. Congregationalism is church ruled by a formal democracy. That can be a mixed bag too.

In both of the history books I am reading, the development of an indigenous Christianity is promoted as having a much more permanent and powerful effect on the people. Demanding doctrinal purity on lots of small details has historically alienated the new excited converts. Africans were very interested in Jesus, but less interested in all the details of Anglican or Roman liturgy, which seemed to have more to do with British Colonialism than God. The same is true with every other group of western missionaries. Ethiopia in particular took a rather isolationist stance. It’s version of Orthodoxy and later Protestant Pentecostalism are pretty unique. Many accounts of the underground church in China also emphasize how little input they have taken from westerners.

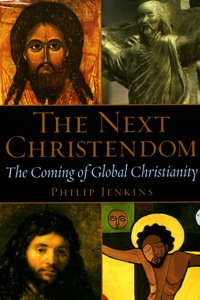

Jenkin’s gives an interesting example here to demonstrate:

We must be cautious about seeing such new movements through the lens of our own conflicts. As an analogy, imagine the situation in the seventh or eighth centuries in what was still, numerically and culturally, the Near Eastern heart of Christianity, in Syria or Mesopotamia. Picture a meeting of church leaders who have gathered to hear a report from a traveler from the remote barbarian world of western Europe.

The traveler delights his listeners by telling them of the many new conversions among the strange peoples of England or Germany and the creation of whole new dioceses in the midst of the northern forests. Impatiently, the assembled hierarchs press him to answer the key question: This new Christianity coming into being, is it the Christianity of Edessa or of Damascus? Where do the new converts stand on the crucial issues of the day: on the Monothelite heresy, on Iconoclasm? When the traveler tells them, regretfully, that these issues really do not register in those parts of the world, where religious life has utterly different concerns and emphases, the Syrians are alarmed. Is this really a new Christianity, they ask, or is it some new syncretistic horror? How can any Christian not be centrally concerned with these issues? And while Syrian Christianity carried on debating these questions to exhaustion, the new churches of Europe entered a great age of spiritual growth and intellectual endeavor.

-Philip Jenkins, The New Christendom, p.16

So how much of this sort of thing is OK? I’m not sure, but I think my initial position is that for a burgeoning Christianity, some of this mixing is not that big of a deal. Immature Christians may have genuine belief in Jesus Christ, but still believe all kinds of silly things on the side. These are rooted out through teaching and love from caring pastors and positive peer pressure. The Holy Spirit will also lead people to abandon their old ways as their hearts change. When these folk elements are institutionalized, then reform over the coming years and decades will hopefully improve things. I believe that it is completely impossible to not mix in something. Only robots could have an untainted faith. Still, some syncretism severely undermines the Gospel by tacking on works righteousness. These elements need to be expelled from the get-go. Our dead works need to be repented of, not integrated.