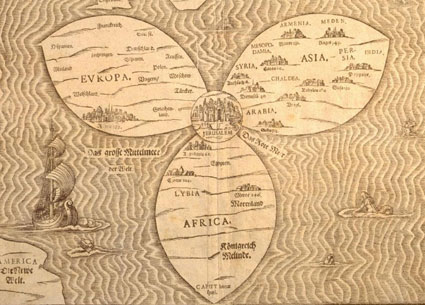

I just finished reading what is, admittedly, my first proper history book. It is The Lost History of Christianity, by Philip Jenkins. Lest you see the title and immediately assume it has something to do with the fruity gnostic gospels that have been all the rage this past decade, the subtitle of the book should clarify things: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia – and How It Died.

So to condense the whole book into just a sentence or two: The Roman Catholic church has never been the only game in town. Large prominent networks of Christian churches existed in the middle east, northern Africa, and in India from very early on (200 A.D.). They even still flourished after the rise of Islam. But then, in the 1300’s…. POOF! Now, we in the west barely even remember they ever existed.

In the final chapter he draws some conclusions. In some places, the church dissolved amazingly fast when persecuted. In other places, it holds on even today. What was the difference?

The difference was how grass-roots the Jesus movement became. In old Morocco and Algeria, cathedrals were built and the church had lots of real estate, political influence, and upper-class followers in the cities. If you read Augustine’s letters, you can see that he was very focused on his one metropolitan center. Christianity never penetrated the many outlying villages and folk cultures. The bible stayed in Latin and was not translated into the vernacular. When the Muslims invaded and the government changed hands, the Christians vanished. Everyone who was left found it easy to convert to Islam since their Christian roots did not go deep.

In neighboring Egypt however, the scriptures were translated into the local language (what we call Coptic) very early on. The whole culture, from the learned to the peasant was steeped in Christianity for hundreds of years. The church was not near as dependent on the hierarchy of bishops. When the ecclesiastic framework collapsed under Muslim oppression, the people remained Christian, even influencing their captor’s own religion in turn.

In the sixth century, some five hundred bishops operated in this region; by the eighth century, it is hard to find any. Ironically, one of the paladins of North African Christianity in the third century had been the prophetic church father Tertullian, who wrote the famous line about the blood of martyrs being the seed of te church; yet some centuries later, this very church all but vanished before the Muslim invaders. In this case, seemingly, the seed had falled on stony ground.

In Egypt, by contrast, which has been under Muslim rule since 640, not only does native Christianity survive to this day, but the Coptic Church has often exercised social and political infulence. Even in the twentieth century, it probably still retained the loyalty of 10 percent of Egyptians.

The key difference making for survival is rather how deep a church planted its roots in a particular community, and how far the religion became part of the air that ordinary people breathed. While the Egyptians put the Christian faith in the language of the ordinay people, from city dewellers through peasants, the Africans concentrated only on certain categories, certain races. Egyptian Christianity became native,; its African counterpart was colonial.

-Philip Jenkins, The Lost History of Christianity, p.34,35

Jenkin’s does a very good job of playing neutral in his conclusions, but it’s impossible for him to not take a jab at the prosperity gospel. Tying our faith to worldly success and wealth is, historically speaking, a sure-fire way to lose all your converts as soon as times get tough. If material wealth and political power are preached as a sign of favor with God, then when the economy tanks or war comes (and it will!) then many will lose faith, or switch faith.

He sees the protestant reformation, with it’s printing press and the placing of Bibles in every hand as a huge step toward making Christianity ultimately conquest-proof, despite the internal strife and factions that it created, and still feeds today.