We have oriented our job market and our universities to train people in doing one single thing very well, to the necessary exclusion of a hundred other important things. The generalist, the wise fox, is scorned and ignored for his lack of credentials, despite the fact that he may easily be the wisest or most clever person in the room.

“The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” – Archilochus, ~650 B.C.

Many of our public institutions are led, not by men of broad understanding or even business acumen, but by men whose only forte is their raw ability to schmooze potential donors. The army is not led by warrior, but by tactician-wonks. They can drop a laser-guided bomb down your chimney, but have outsourced bravery to the special forces and cultural understanding to the diplomats. But of course this is the best way, right? Flying a predator drone is very complicated and hard enough. The pilot can’t be expected to know anything about the people he is watching. He’ll leave that to the analysts.

Actually, talking about the military isn’t the best example. A better example would be to talk about the whole man – not just his work, but his family life, his faith, his community. The classic image of the socially-awkward computer nerd is rightfully worthy of ridicule. So he can write Python code in his sleep, but what kind of father is he? Equally, the socially-savvy Wall Street executive who is never at home? What kind of father is he? What kind of husband is he? Can he sing, dance? Write verse or write a letter to his mother? Is he a good Christian (or good Muslim, etc.), a good citizen? Or is his mostly just a coding machine or a money-making machine?

I think one my favorite passages from Wendell Berry is where he goes after vocational hyper-specialization. He wrote this in the seventies, and if anything, it’s far, far worse today

The disease of the modern character is specialization. Looked at from the standpoint of the social system, the aim of specialization may seem desirable enough. The aim is to see that the responsibilities of government, law, medicine, engineering, agriculture, education, etc., are given into the hands of the most skilled, best prepared people. The difficulties do not appear until we look at specialization from the opposite standpoint – that of individual persons. We then begin to see the grotesquery – indeed, the impossibility – of an idea of community wholeness that divorces itself from any idea of personal wholeness.

The first, and best known, hazard of the specialist system is that it produces specialists – people who are elaborately and expensively trained to do one thing. We get into absurdity very quickly here. There are, for instance, educators who have nothing to teach, communicators who have nothing to say, medical doctors skilled at expensive cures for diseases that they have no skill, and no interest, in preventing. More common, and more damaging, are the inventors, manufacturers, and salesmen of devices who have no concern for the possible effects of those devices. Specialization is thus seen to be a way of institutionalizing, justifying, and paying highly for a calamitous disintegration and scattering-out of the various functions of character: workmanship, care, conscience, responsibility.

-Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America, p.12

It’s not just the instructional side of higher ed that has been unbalanced in this fashion. The research side has mutated as well. I hadn’t heard of this before, but it’s really interesting and makes a lot of sense. Thanks to John H. for mentioning this in some comments about Zizek.

This ties in with a point Slavoj Zizek made in his lecture yesterday concerning how most major advances in knowledge are made “inadvertently”: you set out to investigate one thing, but then discover something far more significant that you weren’t expecting. He argued that modern academic funding relies too strongly on researchers finding exactly what they set out to find, and has no space for the accidental or contingent discovery “on the side”, as it were.

All that research grant money has rules tied to it that dictate exactly what you must try to figure out. Unexpected or valuable discoveries that may cross disciplines are choked off. Some companies, like Google, have tried to explicitly remedy this situation by letting employees spend 10% of their time on hobby side-projects of their own creation. This has ultimately led to the invention of some of their best and most innovative new products and services. We need more of this in higher ed, which is to say, we need fewer specialists and more renaissance men – more foxes and fewer hedgehogs.

“You’d be crazy to work in a school today. You don’t get to do what you want. You don’t get to pick your books, your curriculum. You get to teach one narrow specialization. Who would ever want to do that?”

-Steve Jobs (from an interview with Wired magazine)

The philosophy of modernity that has largely been driving this change is pragmatism. Pragmatism says that if it works, then it must be true. This drives technology. The technology advocate will always take an isolated case where the “new thing” can be proven to “work” better than the old thing. He implies that it is superior in the context of life and humanity, ignoring the fact that the new technology’s superiority was demonstrated in a vacuum. Eugenics works amazingly well – when you don’t consider any of it’s social side-effects. Out-sourcing your customer support to India is also a no-brainer – if you you are adept at missing the forest for the trees. The cheap plastic product will save you money today, but not later after it wears out quickly. “Teaching to the test” will give your students a better score on that state-mandated multiple-choice marathon, but they will grow to become more shrewd thinkers for having studied the classics (that weren’t on the test). Pragmatism is specialization in action. Powerful but nearly always short-sighted.

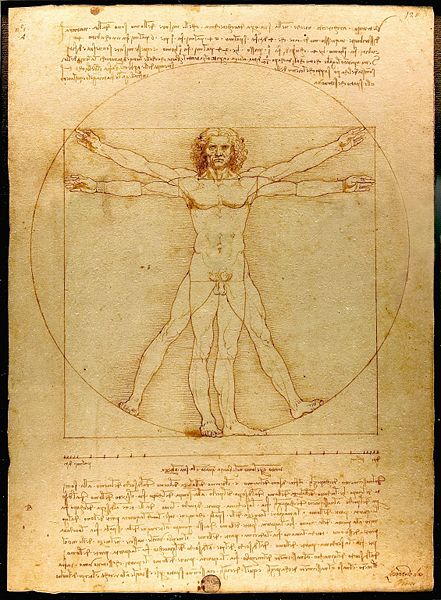

Why am I even writing this? Because I believe the dream of the reniassance man is REAL – not the famous astound-the-world renaissance man like Da Vinci, but the average Joe everyday type. Learning skills are NOT a zero-sum game. You don’t have to choose between being great soccer player and playing the violin, seeing each hour of the day as finite and unrecoverable. You do not need to forsake your wife and family to be an effective artist or CEO. You do not have to be a monk or a pastor to be a holy man (or woman). Your brain isn’t a bucket that only holds a fixed amount of knowledge – it is a muscle that grows in strength as you exercise it.

The work you do in EVERYTHING in life, even areas that are seemingly unrelated, will strengthen you as a whole, as a person. Learning to be patient with your children will make you a better manager at work then any MBA program. Learning to play the French horn will make you a better programmer. Reading literature will make you a better construction worker. Go to church, and you may hear the good news that all your pitiful efforts will not save you, but that, never fear, you’ve been saved already.

Neglecting an area of health (physical, mental, spiritual) has great negative implications for the other parts. The hyper-specialization of our vocations has made this the accepted norm. Recovering a respect for the generalist, and learning to follow in his footsteps, will ultimately stand to strengthen, enrich, and wisen our culture and society again.