Earlier today, Joshua Gibbs wrote:

“If a thing is not transcendent, it is arbitrary.”

Now I think I’ll attempt to apply this to language for just a moment. As I stare at my only partially-tackled bookshelves, I am sharply reminded of the great multitude of thought on this topic that I am ignorant of. Nonetheless, I think I can still explore a few worthwhile avenues with what I have.

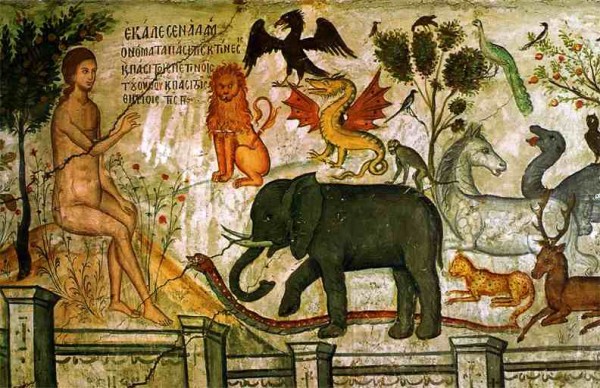

Is the naming of a thing arbitrary? Man is an absolute whiz at naming things – God created him this way and gave him the task of naming everything long before the fall. In the millennia after, he has not ceased to categorize everything. With man, it’s all naming all the time. But is his naming arbitrary? Is he just making crap up out of thin air, like a database assigns pseudo-unique GUID’s to each record? Here’s an example: {96ac1fe6-032c-4df5-9620-5772b37365c2}. Are our names just like that, or are they rooted in reality, the natural, or as we might say, the transcendent?

“I am Gandalf, and Gandalf means me!”

– J.R.R. Tolkien

Notice Tolkien does not have him say “My name is Gandalf”. He is unique and his name means himself, which, to some degree means that himself means his name. Tolkien writes this even while explaining elsewhere that his “real” name (or at least older name) is Olórin. Tolkien names everything in his world carefully based first on what they are.

He even offers some commentary on this own craft at times. Consider this passage about Beorn from The Hobbit:

“And why is it called the Carrock?” asked Bilbo as he went along at the wizard’s side.

“He called it the Carrock, because carrock is his word for it. He calls things like that carrocks, and this one is the Carrock because it is the only one near his home and he knows it well.”

Why is that thing named such? Gandalf’s answer is, that as far as he is concerned, the name is arbitrary. Beorn called it that, so that’s what it is! He knows it well (and probably even built it), so he get’s to name it and the rest of us will use that name too. But it is sort of made up. Or maybe Gandalf is just admitting that he doesn’t know exactly where the word comes from. He doesn’t know the history or reason for it’s name, but he assumes one exists.

I don’t think anyone will deny that language is rooted in history. That words grow out of other words is not up for debate, even if it is frustrating to those trying to stretch language in new direction.

“When I use a word it means just what I choose it to mean” (Humpty Dumpty, from Alice in Wonderland)

Like Humpty Dumpty, Stephen [Joyce’s autobiographical protagonist] would like to exert complete mastery over language and meaning, but his experience consistently brings home the fact that none of us has such power. He may complain, in Ulysses, that “history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” but he realized that he must do so in a language conditioned by that very history.

-Kevin J.H. Dettmar, Introductory notes to James Joyce, p.xxv

And from this one can jump straight into some thought by Derrida or other post-modernists. What they essentially did was to follow this line of thinking to it’s logical end and conclude that all words are indeed arbitrary – not transcendent. There is no real meaning to be found in anything. Sure our words now are based on meaningful older things, but if you go all the way back to Adam, he’s just making crap up. Zebra might as well be {c4786612-6c21-4574-bc8f-d8c6c52775cb}, Fox {a3386dfe-7e82-4ec1-baf0-71b91bb9da47}, etc.

But, if we are theists, we must believe their is a transcendent underneath our words. If we are children of Abraham (formerly Abram!), we must say that a name is there for a reason – a reason that is not just more piles of slippery words. If we are Christians, we must believe that the words God speaks transcend even lips or ink. One time they even walked around on the earth and bled on the ground. There are good names, and there are evil names because there is real good and real evil. And the thing came into being first and then was named. Man may resist or “deconstruct” as much as he might, but most of the time he will still end up giving appropriate, that is natural, names to things.

Update: A good piece related to this here.