I’m certain someone has thought of this before, but I don’t recall having heard it put exactly this way before, so I’ll give it a shot.

Science is held in extremely high regard in the modern world. It would be more accurate to say that the “idea” of science is held in high regard. Proper science of the strict and ruthlessly inquisitive sort is on the wane in the academy and can rarely be assumed to be behind many claims and ideas that smell science-y today. Regardless, science is respectable in the extreme in public.

All people have problems in their day-to-day lives – in their jobs or in their relationships – problems they try to solve and situations they try to understand. When trying to understand a problem, what tools do you reach for? You might reach for empathy, an extremely useful psychological tool. You might reach for patience or trust, something that we might put under the category of “spiritual discipline”. You might reach for your own physical strength and constitution to push through the situation. But one thing that often comes to mind in our present age, an age where science is king, is to leverage science to help solve our problems. And what is the easiest way to seemingly understand something in a science-y way? With statistics and probability.

Instead of asking, “What does this person care about?” We ask questions like, “What is the likelihood this person will get angry at me if I do such and such?” 40%? 70%? In a sample of the couples at this party, 3 out of 18 of them have prettier girlfriends than I do, so I guess I should feel pretty good about my situation – it’s well above average. For my presentation, it’s critical that I tell a joke before the 2.5 minute mark to keep people engaged. According to my food journal, I sleep better on the Tuesdays when I don’t eat gluten.

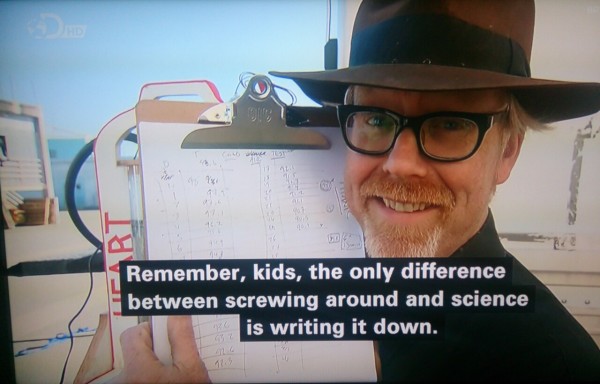

These are all just observations about the world of the sort that we all make all the time. The difference is that we now tend to express them in scientific jargon to enhance their power. If we can borrow some of the aura that put a man on the moon or that makes the 128 gigabytes of memory in our iPhone work, maybe it will help us be a better parent too or enable us to make wiser life decisions.

Earlier in history, these lines of thinking or intuitions were more likely to be described with qualitative words. Now we are more apt to use numbers. The way we describe the world and even think about the world has appropriated this new vocabulary. The problem is, that vocabulary was meant to stay in a roped-off arena and not brought into the mushy and bewildering land of human beings and ad hoc impressions. As we’ve now done this for several generations, some of the mushiness has oozed BACK the other direction. We think we are science-y about everything, but in fact we are often less so than ever before.