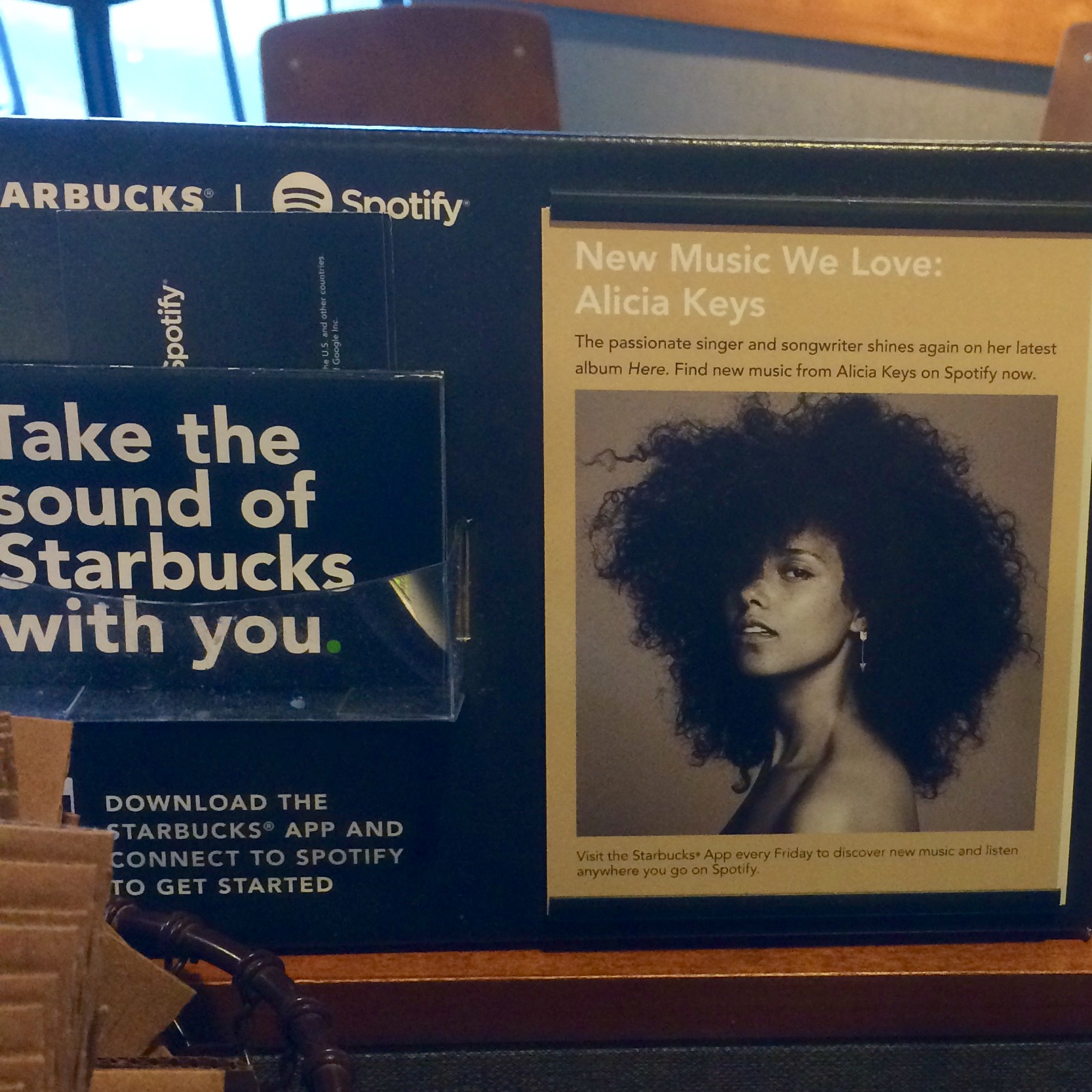

This placard was displayed near the cream and sugar at the local Starbucks yesterday:

“New Music We Love” next a promo photo for the new Alicia Keys album. But this is not a particularly faithful caption. It would be more accurate to say, “We are being paid a suitcase full of cash from RCA Records marketing department to promote this album in our 20,000+ retail locations, so here you go!” Whoever “we” is doesn’t “love” this music, however good it is, any more than they “loved” whatever the people in charge of shop decoration were being paid to promote last month. This doesn’t come as news to anyone of course. We are saturated in a world of marketing and advertising, now more than ever. We are, in theory at least, aware of it even as we swim in it. It’s been lamented and commented on by people of every persuasion in essays for decades now.

Even as far back as 1955, we find Merton discussion the same thing:

Do we know what it means to praise? To adore? To give glory? Praise is cheap today. Everything is praised. Soap, beer, toothpaste, clothing, mouthwash, movie stars, all the latest gadgets which are supposed to make life more comfortable – everything is constantly being “praised.” Praise is now so overdone that everybody is sick of it, and since everything is “praised” with the official hollow enthusiasm of the radio announcer, it turns out in the end that NOTHING is praised. Praise has become empty. Nobody really wants to use it.

Are there any superlatives left for God? They have all been wasted on foods and quack medicines. There is no word left to express our adoration of Him who alone is Holy, who alone is Lord.

-Thomas Merton, Praying the Psalms, p.10

The extreme overuse of the word “awesome” is maybe the best example of the kind of language degradation Merton is talking about here. Think of how much this has intensified sixty years too. Merton himself would barely live long enough to see the advent of color television.

In his survey of postmodernism, Leithart addresses this same phenomenon in which this ubiquity of “praise” has corrupted language and communication at a deep level.

Communications media encourage a skeptical cynicism toward knowledge in general. Especially in urban settings, many of us are “supersaturated” with media and advertisements, bombarded by messages from anonymous sellers and senders whose only interest in us is our credit card limit. The proliferation of anonymous messages tempts the thought that messages exist independently of persons, that the messages are not communications but mere “texts.” The “death of the author” proclaimed by postmodern theory is partly a recognition that the author vanishes to nothing in contemporary media. Try this test: Can you list three advertising taglines? Then, can you name a single advertising copywriter?

-Peter Leithart, Solomon Among the Postmoderns, p.64

At first glance, this can all be rather discouraging. I know that personally this has been the source of much angst over the years. How can we sing Jerusalem’s praise in a strange land where our “awesome” words have no meaning? The best worship we can bring seems trite and dead on arrival.

I’ve heard a variety of prescriptions over the years to combat this. One is to “plunder the Egyptians” and make sure Christian music and culture really kicks ass. If you love the many-layered synth production on the latest Hillsong United album, then you might still think this plan shows promise. Many of us are not particularly convinced, for all kinds of historical reasons, not to mention a few theological ones.

Another attempt is to recover the golden age of high Christian art, studying and singing the works of Bach and the best harmonies from Tallis to Beethoven. This can feel rather fabulous within its ecosystem of trained singers and listeners, but like a foreign static to the bulk of our neighbors.

Ah, so our neighbors need to be educated! Fixing education, bringing back great books, classics, and doing the true work of education as Aristotle described it, “to learn to love what one ought to love”, is the way. If we can heal our trashed and abused language, then we’ll be able to call pizza another word besides “awesome” again so all the Holy praise can come back to life in contrast.

I’m not really against any of these aforementioned ideas, but I have difficulty maintaining my enthusiasm for them. They all sound like a lot of work – a strenuous uphill climb that seems to take on a life very much apart from the Gospel of Christ, which somehow manages to meet us in our lowliest state, even with f-bombs and other curses on our lips.

And so I was encouraged to find a different prescription from Merton: to pray the psalms. He is convinced that they still (and will permanently) transcend any defects our language and listening may acquire. Heavy scholarship is not required, only a very little faith.

The Church indeed likes what is old, not because it is old but rather because it is “young.” In the Psalms, we drink divine praise at its pure and stainless source, in all its primitive sincerity and perfection. We return to the youthful strength and directness with which the ancient psalmists voiced their adoration of the God of Israel. Their adoration was intensified by the ineffable accents of new discovery: for the Psalms are the songs of men who knew who God was. If we are to pray well, we too must discover the Lord to whom we speak, and if we use the Psalms in our prayer we will stand a better chance of sharing in the discovery which lies hidden in their words for all generations. For God has willed to make Himself known to us in the mystery of the Psalms.

What God has willed to make known to us through his particular gift of the Psalter, no mass media flood or deconstructionist philosophy can thwart. Our verbalization and reenactment of it is a clear way forward through the fog.