In my recent travels to Ethiopia, I ventured out of the capital into Oromo territory for the first time. The Oromo are the largest ethnic group within Ethiopia, making up 35% of the population – over 35 million people. My daughter, as well as many other Ethiopians I have met are Oromo or at least partially so even if their names are Amharic. In the rural areas, this distinction often still matters and not all the groups get along with each other. As you near Addis Ababa, the capital, ethnicities melt together and it can be difficult to distinguish between Oromo, Amhara, Tigray, and other groups. I had several people tell me in Addis that it is just something that doesn’t come up in conversation there. One man told me that he didn’t know (or care) about his wife’s ancestry and only even learned the details after they were married. In the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the city, it can sometimes be difficult to relate to the political unrest experienced more sharply in other parts of the country.

One area where the distinction still obviously exists is in their language. The Oromo are proud of their language and though many of them learn to speak some Amharic (everyone I met could to varying degrees), they will still speak the Oromo language primarily. The official name for the language is “Affan Oromo”. “affan” means ‘tongue’. Almost the same word, “aff” means “mouth” in Amharic. What I found though is that everyone there calls it “oromifa”, which is funny because this word is not even mentioned in the long Wikipedia article on the subject or any of the guide books I have, but seems to be the dominant name on the ground.

The organization I have been working with, Zena Wengal, has fortunately been able to acquire many braille copies of the Amharic bible for blind Christians there. Lutheran Braille Workers is a wonderful organization and has been able to supply them with many copies over the past few years. Keep in mind that an Amharic New Testament is 33 volumes in length, so this means thousands of volumes. Someone did the work of properly transcribing and formatting the Amharic bible into braille some years back, and so they have all the files to emboss at hand.

There are many blind among the Oromo though and they need a braille bible in their own language! A tiny handful have access to audio bibles, but the bulk cannot study the scriptures at all on their own. They must have someone read to them. Yes, the most educated among them could hack their way through an Amharic copy, but the symbology is completely different and the vocabulary relatively advanced for someone who just uses Amharic as a second language occasionally.

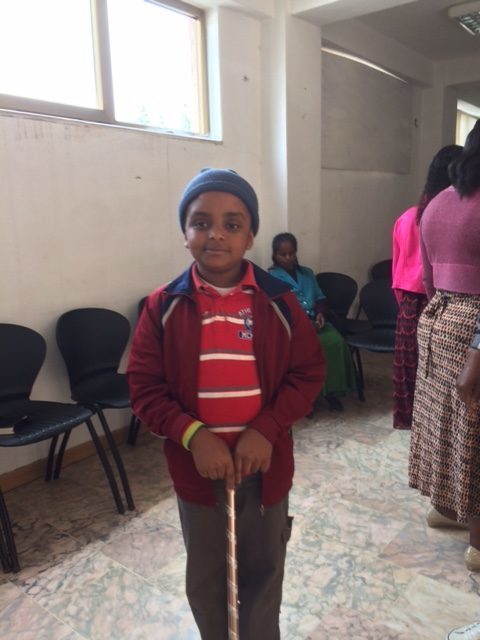

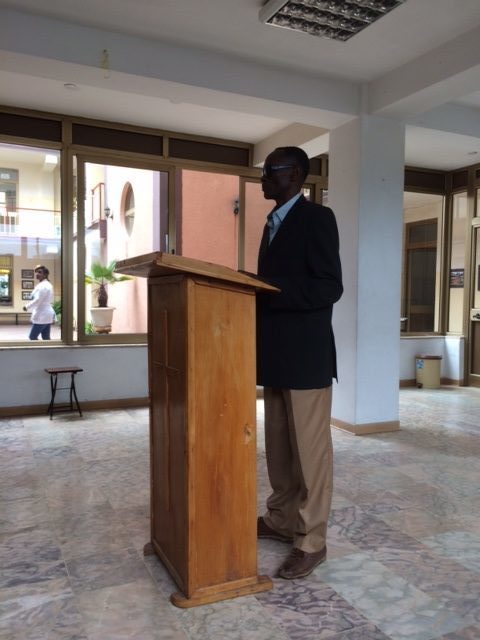

(Photo: Over 50 Oromo men and women gather at a Zena Wengal service at a church in Sebeta on December 17, 2016.)

So with all this in mind, I set out to get a hold of some copies of Oromo bibles in braille to send to my friends there. You can find anything on the internet right? Well, not really – not if it doesn’t exist! That’s right, they don’t exist. I’ve talked to a lot of people and hunted down every online trail I could and I’m pretty confident that none have ever been produced. (I would love to discover that I’m wrong!) If any exist, (and I think it likely one at least partially exists somewhere, though I haven’t been able to confirm), it must have been a unique one-off printing.

Compass Braille, located in the UK, has expressed interest in producing an Oromo braille bible. It’s on their shorter list of new languages to transcribe and format, but after speaking with them, it doesn’t sound like it’s going to be done any time soon. It could easily be years away. In the meantime, Lutheran Braille Workers doesn’t have the money and personnel to do the job. They are busy filling a large demand for Spanish braille bibles in South America this year and next. It turns out that LBW and Compass are really the two big producer’s of Christian braille materials for the blind on earth. A few other small organizations have come and gone. It seems they have an unofficial agreement not to step on each other’s toes. Their mission is certainly the same and they both operate entirely by donation, often working closely with the International Bible Society to fill larger orders.

This required me to split my mission. In the short-term, I’d like to get a copy (or several copies really) of at least the Gospel of John in Oromo to my friends there sometime in the coming year. In the longer-term, I’d like to help get the Oromo scriptures transcribed into braille, either by assisting with the process directly (with my wife who is a certified braille transcriber), or by perhaps helping to personally fund and/or petition for Compass’s attention to turn that direction sooner rather than later.

I’m going to record my efforts here on my blog for fun. Someone else searching for info on the same thing or trying to accomplish something similar with another language may find it helpful in the future.