It seems to me that religious communities will typically embrace a theology that make the most sense in their given social and economical context. If they are wise, they acknowledge that they are doing this while they are doing it and admit that the theology might take a significantly different shape, given another context. The next generation though is often taught that the shape their community has taken is sourced directly from scripture and validated by old (Reformation era) or very old (early church fathers) authoritative commentary. The next generation is of course, in theory, aware that their social/economic/cultural setting has ordered some of their beliefs, but they do not realize to what extent. Seemingly finding their grounding in scripture, they believe themselves to be primarily shapers rather than the shaped.

This weekend, I visited a friend and his large family who had moved away about a year ago to take a job in a city 2 hours away. Though he was very active in the same denomination, he commented how different the character was, it no longer being centered in a college town. When the congregation is comprised of hundreds of students, from green 18-year-olds to newly married graduate students, and the elder board comprised largely of professors or higher-ed administrators, the life of the congregation takes a rather peculiar form. It affects everything – the sermons, the rhetoric, what ministries are emphasized and most funded. All of this comes back around to shape biblical interpretation too. It happens within the bounds of the denominations beliefs, true, but it can skew heavily in particular directions.

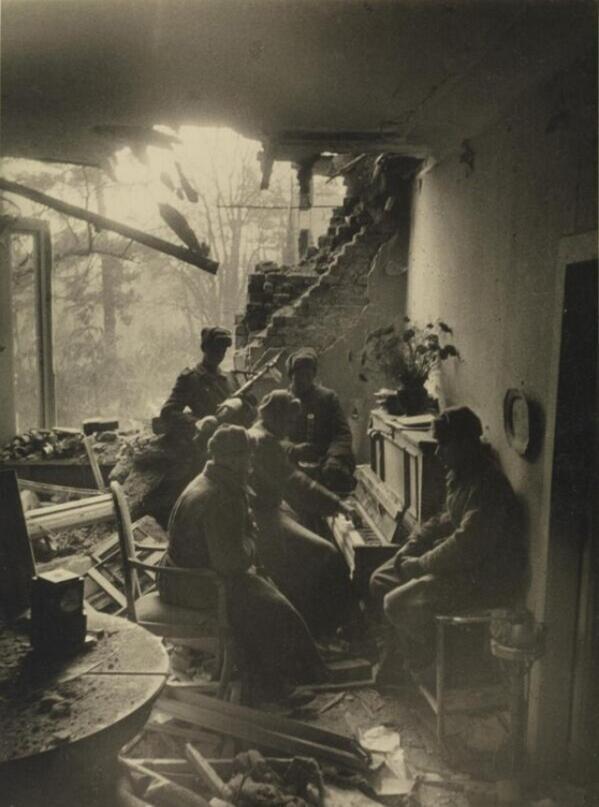

The place my friend lives now is much more blue collar and the city less walkable. There is a lot less socializing – everybody is busy with their jobs and lives too far a drive away to visit casually. The local university is not there to provide a unified workplace (and source of salary) and close living quarters. Conversations rarely tread into graduate level higher criticism or that thesis you are working on about Augustine’s City of God. Instead, they stay centered around who is in the hospital, when the troublesome freeway detour is going to be completed, and where the best place to take the kids fishing is this year. Hundreds of topics that previously seemed to be of world-shaking importance are now completely off the radar.

All these different things swirling around you change what you think about when you go to pray or read scripture. The Holy Spirit also knows what you need and will speak to you about what is present in your life at the moment (unless of course he is calling you elsewhere or waking you up to a new possibility). The end result? Your theology changes and as your memory fades, you may forget how very different life can FEEL in other times and places, even ones not terribly far away.

Skeptics and secularists will point to this phenomenon as simply evidence that religion is nothing more than a social construct – entirely subjective and imaginary, though of course “deeply meaningful”. Recent fad theologians will observe this and call in “incarnational”. Woopie. I think I’ll just call it “natural”. It’s geography taking it’s toll, no matter how fast our internet flies. It’s how people work to get their food making a big difference in their day to day lives, just like it always has everywhere, despite state’s efforts to diversify, subsidize, relieve, or incentivize

I think the right response for us to have mercy and grace on our fellow Christian. Their life is different from yours – probably more than your realize and there is probably less they can do to change it than you think. Throw them a bone and start by giving them the benefit of the doubt before you dismiss their theology as having missed the boat compared to yours. Yes, it’s entirely possible that it’s full of holes or that they’ve run off the rails in some way, but give empathy a shot.